The Story of Progress (and Education)

What is an aardvark? When was the moon landing? Where is Mount Vesuvius? When I was a child, I would look for answers to these questions in the World Book Encyclopedia. Complete with red leather binding and gold leaf, it was one of my family’s prized possessions. I would pull the appropriate volume off the shelf, flip through the pages in hopes that there was an entry, and read through it looking for the tidbit of information that I needed.

By the standards of the 80s and 90s, that World Book Encyclopedia was a wonderful resource, but in today’s world of Google, Siri, Wikipedia, and the host of other tools clamoring to provide you with instant answers, well… my trusty World Book falls pitifully short.

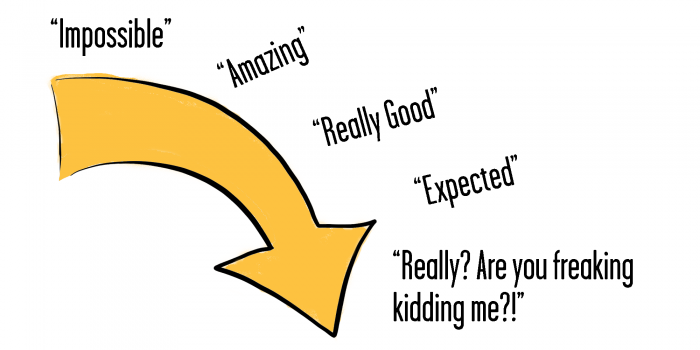

This new world of technology-aided omniscience is so pervasive that it has completely changed our expectations around what is and isn’t reasonable. We’re past the point of awe or wonder, and even past the point of really appreciating our pocket-sized oracles. Now we just expect it, and even a second of buffering delay, or the occasional question that stumps Siri, leads to bemusement and annoyance.

This, my friend, is the story of progress.

It begins with a change that allows us to accomplish what previously was relegated to fantasy or science fiction. Think of the Wright Brothers proving that powered human flight was possible in 1903, Neil Armstrong landing on the moon in 1969, or the sequencing of the human genome at the start of the current century.

That sense of wonder doesn’t last long. We adapt, and soon marvel is replaced with appreciation and desire. It’s no longer impossible… it’s just the best available, and—to the extent that we can afford it, of course—we want it! This was commercial air travel around the time of the First World War, personal computing in the late 70s and early 80s, cell phones in the 90s, and electric cars over the past decade—doing double duty as great wonders of technology and convenience, and great symbols of luxury and status.

Progress continues its inexorable march forward. What was “best in class” gradually becomes the baseline of “good” service. We take it for granted as table stakes, and notice it only by its absence. Good examples include anything that we think of as a utility, like electricity, indoor plumbing, phone and cellular service, and basic Internet access. We don’t marvel at a home complete with electricity and indoor plumbing, but we fume when our toilets back up, or we can’t run an appliance without blowing a fuse.

Eventually, what was once new and shiny becomes old and lackluster. These are the things that are still with us even though they really shouldn’t be, that elicit reactions of, “Really? Are you freaking kidding me?!” Whether it’s obtuse government bureaucracy, hotels that charge $15 a day for Internet access, or those motion-activated faucets in airport bathrooms that can’t seem to tell when your hands wave in front of them… they exist only because nobody has gotten around to fixing or replacing them, and we all know it’s just a matter of time.

This is the story of progress, and also the story of education.

Modern education dates as far back as the eleventh and twelfth centuries in Europe1 and the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in North America.2 Almost everything about education has changed since those days, from the diversity of those consuming it (including men and women of all races and social strata) to the range of institutions providing it (not just the thousands of accredited universities around the world, but also K-12 education, continuing and executive education, alternative education, online courses, and more).

But the most important thing has remained constant: the promise and expectation of a better and more successful life upon graduation. Whether it was the very first official diploma awarded by Harvard University in 1813, a modern-day undergraduate, graduate, or post-graduate degree from an accredited university, or the slew of alternative and supplemental options that have emerged in recent decades, the core premise that justifies your enrollment (and their existence!) is that the trade of your time and money for their experience and certification will leave you smarter, wealthier, happier, or otherwise better than you were when they found you.

As measured against that benchmark, education has had a pretty good run. Once just for wealthy aristocratic elites, the twentieth century saw a surge in the number of people aspiring to the solid career and comfortable middle-class life that a university diploma offered. And for a while it delivered, and then some. A university degree, the archetype of modern education, was the golden ticket to success. If you were so lucky as to have the opportunity to get one, you knew that the lifetime benefits would outweigh the cost of money and time by orders of magnitude.

That was true for a long time, but somewhere during the shift from the twentieth century to the twenty-first, things started to change.

Education Isn’t Keeping Up

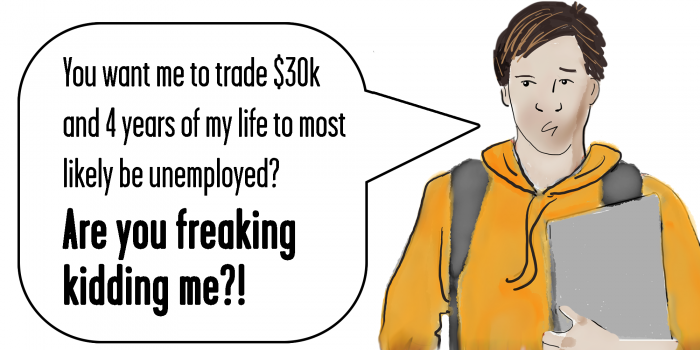

Part of it was education’s inability to keep up with the rapidly changing world for which it purports to prepare us; many of the hottest jobs of today didn’t exist as recently as 15 years ago.3 Another part of it was simple ubiquity undermining differentiation; if you’re the only job applicant with a university degree, it gives you a huge advantage, but if every applicant has the same degree, it doesn’t help you all that much. For these and other reasons that we’ll explore, conventional education simply isn’t the path to gainful employment that it once was; as of this writing the majority (yes, the majority!) of recent college graduates are either unemployed or underemployed,4 and of those who do land jobs, only about a quarter find work in their fields of study!5

Conventional education simply isn’t the path to gainful employment that it once was.

These disappointing returns are set against the rapidly rising cost of education, and the correspondingly crippling debt that graduates must carry. As of this writing, graduating university students in America carry an average debt of $30,100,6 which doesn’t even account for the opportunity cost of going to school and not working full time.

So take the meager returns of modern education, add the soul-crushing debt carried by its graduates, and compound it with the projections that by the end of the next decade college tuition will grow to well over six figures per year,7 and the only reasonable response is: “Really? Are you freaking kidding me?!”

That college costs too much and delivers too little is a problem on many levels… but this is about more than just college. This runs deeper, to the goal of success and upward mobility that college is expected to serve. As recently as a few decades ago, there was a reliable formula for achieving those things in the developed world: As long as you work hard and get an education, you’ll be just fine.

But increasingly, that isn’t the case. While it’s true that undergraduate and graduate degree holders earn substantially more than their peers on average, if you take Ivy League and other top schools out of the equation,8 as well as a limited set of vocation-granting degree programs9 (think engineering, computer science, medicine, etc.), the disparity is much smaller. The data are further skewed because college graduates tend to be concentrated in major population centers, where the cost of living (and therefore wages) is higher, and the large student debt burden drives a disproportionate percentage of graduates to more lucrative but perhaps less desirable fields like consulting and investment banking—which is why so many enter these fields only to burn out of them within a few short years. On top of all that, most post-college earning data are collected by voluntary self-reporting, which skews toward the graduates who are doing well and want to talk about it!

As a society, we think of a university diploma as the ticket to gainful employment, but that isn’t supported by the data. If you adjust for all these factors, much of the difference in lifetime earnings disappears. This is surprising to many, whose impressions of the return on a university investment was formed decades ago. Things have changed since then, and the perception of a degree as prerequisite for entering the job market is simply no longer accurate. And weighed against the rapidly increasing cost, it doesn’t take a financial genius to realize that it just isn’t worth it.

So if the modern college diploma isn’t the golden ticket to the good life… then what is? A slew of educational options have emerged in recent decades. Some attempt to replace college altogether, some attempt to bridge the gap between a college degree and meaningful employment, and some are intended as supplements to a traditional educational path. Here’s a sampling of the things that are available for the modern learner to choose from:

- Repackaged university courses from companies like The Great Courses or on free massive open online courses (MOOCs) like Coursera and the Harvard/MIT collaboration edX.

- Intensive coding bootcamps at outfits like General Assembly.

- Continuing or executive education programs offered by universities and private institutions.

- Recreational courses offered at community centers.

- For-profit colleges of dubious credibility and standing.

- Courses from celebrity instructors on sites like CreativeLive and MasterClass.

- Corporate internal training centers and “universities.”

- Self-study e-learning programs, apps, and software.

- Supplemental education videos on sites ranging from YouTube to Khan Academy.

- Online video courses presented by individual experts on teaching marketplaces such as Udemy and Udacity, or privately on their own platforms.

The list goes on and on… and on. But what has come of all these options?

Overall, the results are patchy and disappointing, but there are bright spots, which we’ll explore in this book. Taken as a whole, though, the landscape of education is fragmented, ineffective, and overpriced; by and large, people are paying far too much for far too little. The broken university system is a prominent part of the problem, because it represents close to half of the $4+ trillion global education market.10 But it’s the entire market that’s broken, not just college.

Fundamentally, we no longer have a place that we can reliably go to become valuable to (and valued by) the rest of society. That hurts so many of us, in so many different ways.

In a World of Broken Education, We All Lose

The current dysfunction of education is so egregious because it hurts so many of us. Most obviously, it hurts the graduates who find themselves with a degree that has practically no market value, forced to make ends meet as Starbucks baristas or Uber drivers.

We no longer have a place that we can reliably go to become valuable to (and valued by) the rest of society.

It hurts the bearers of a combined $1.4 trillion of student debt.11 For those keeping score, that’s more than credit card debt… and unlike credit card debt, you can’t even declare bankruptcy and free yourself of the potentially lifelong consequences of a bad decision you might have made as a teenager.

It hurts the employers who are starved for talent. Education hasn’t prepared job seekers with the skills to fill more than six million open jobs in the United States alone, even as almost seven million Americans are unemployed and looking for work.12

It hurts the learners who seek alternatives. They waste enormous amounts of time and money bouncing between a host of imperfect options like MOOC programs with completion rates that max out at 15 percent,13 overpriced continuing education programs offered by universities, and courses provided by private instructors of varying quality.

And it hurts educators and learning professionals. They labor heroically to brighten their students’ futures, but often that their best efforts can’t overcome the inertia and challenge of the systems in which they operate.

We all hurt from the broken nature of modern education, that no longer prepares us for success. And we all need a solution that is more than just a band-aid.

Thankfully, such a solution exists. That’s what this book is about.

Before we consider the how of a solution, we need to know the what.

“Education that works” could mean any number of different things to any number of different people. Is it about certificates, degrees, and diplomas? Alumni networks and student life? Student experience and satisfaction? Courses and curricula? Competencies and learning objectives? Job prospects and financial return on investment?

For our purposes, “education” and “learning” will be used somewhat interchangeably to refer to the designed experiences that are meant to act as a short-cut to achieving whatever job prospects, financial rewards, upward mobility, social contribution, and personal fulfillment we might aspire to. The short-cut quality is important; if the educational experience doesn’t reduce the time, money, or risk that it takes to get to where we want to go, then we’re better off without it!

And what does it mean for education to “work”? Just that these outcomes be delivered reliably. That means for most or all students, and certainly not just for a minority or the outliers. It’s not enough to say that some students succeed because they go to exceptional schools. Some people are exceptionally successful in spite of their education, or some find success through alternative paths like self-directed learning or entrepreneurship. When the fringes and outliers are the only ones achieving success, they do so in spite of the system rather than because of it.

We can’t be (and aren’t) satisfied with the old quip about education being the transfer of ideas from the teacher’s notes to the student’s notes, without passing through the head of either. Yes, we must impart knowledge and corresponding skills. That’s a great start, but only one of the three key drivers that empower us to succeed. We must also impart the practice of developing meaningful insight, and support the balance of emotions and habits of fortitude that are needed to succeed through education, and the rest of life.

All of this must be done cost-effectively, too—meaning without breaking the bank, saddling anyone with back-breaking debt, or otherwise requiring an investment that simply isn’t justified by the promised outcomes or the process it takes to deliver them.

That we should have (and have access to) an education that works might seem like a self-evident no-brainer, except that it is so frustratingly far from the world in which we now live.

So to arrive at an education that works, we have quite a lot to explore…

This book is written for two types of people: the lifelong learners who consume education—and I’ll argue that lifelong learning is less a matter of passion or recreation and more a simple requirement of relevance in this modern age—and also for the educators and learning professionals who work hard to provide it. And of course, many of us fall into both categories!

Our first task, which we’ll undertake in the first half of this book, is to understand why education isn’t working, and what needs to change. We’ll explore this in five chapters:

- Why Modern Education Is Ineffective, Overpriced, and Ubiquitous – This has as much to do with signals and bubbles as it does with the substance of that education, with frightening implications for degree-issuing institutions and their graduates.

- Education for the Age of Acceleration – Exploring how our world is changing (think artificial intelligence, automation, intelligent appliances, and driverless cars), and what education must offer in order for us to stay relevant.

- The Changing Landscape of Learning – Here we’ll explore the four major transitions that are changing almost everything about the way we consume education.

- Economics of the New Education – This exploration will get us to the root of why today’s higher education is hamstrung by money, and where we can expect education to come from in the future.

- Learning from the Experts – Finally, we explore the economics and educational requirements that lead us to the unlikely source of continuing education in the modern world.

Having firmly established exactly why the education of yesterday can’t prepare us for the world of tomorrow, we’ll roll up our sleeves and dig into what it will take to get it right. This begins with the art and science of human learning: what it entails, how it works, where it shines, and why it sometimes breaks down. Then we’ll focus on the matters that are especially relevant to the creators and purveyors of education:

- Knowledge: Making It Easy For People to Learn – This is all about memory and skill, and we’ll explore why it can be so fickle and elusive, and how to accelerate and shortcut the process.

- Insight: Where Critical Thinking Meets Creativity – We’ll explore what insight is, why it is so elusive, and how to cultivate it.

- Fortitude: How the Tough Keep Going When the Going Gets Tough – This is the hidden ingredient that keeps the tough going when the going gets tough. We’ll explore why learning short-circuits for so many people, and what it takes to create a better script and outcome.

- Designing Great Courses – Here we’ll shift gears from the art and science of learning to a practical process for building courses that serve the needs of modern learners.

- The Six Layers of Leveraged Learning – These are the pieces that go into building a world-class learning experience, from the content that you’ll cover, to the success behaviors that you’ll instill, the way that you’ll deliver, the user experience that you’ll create, and the accountability and support that you’ll provide.

So yes, I’m hoping to do quite a lot with this book! And like any ambitious endeavor, it deserves a disclaimer or two.

Directionally Correct (Is Better Than Perfectly Accurate)

Let’s start by being upfront about the fact that each of the many topics I just mentioned is broad, rich, and substantial, so much that every chapter could easily be expanded to an entire book—or several!

But this isn’t that sort of book (or series). I’m not an academic, a researcher, or a journalist. I’m an educator and an entrepreneur who has had a lifelong love-hate relationship with education. I dropped out of high school, and went back to earn a graduate degree from a top school. I built an education company—not because of my degree, but rather in spite of it. And I’ve built a career on designing education that makes a real difference in the lives of my students. This book draws on the lessons that I’ve learned along the way. And while this book is well researched, its focus is pragmatic rather than scholarly, designed to help you move in the right direction now, by choosing directionally correct, useful, and immediacy over perfectly accurate, academic, and unavailable information for several more years.

For that reason, this book addresses the world of education with a fairly broad brush. Higher education will receive a good deal of attention, along with executive and continuing adult education, vocational training, independently provided in-person and online courses, and everything in between. Although the focus of this book isn’t K-12 education (both because it isn’t my expertise and because overabundant regulation makes it extra hard to do anything about influence), I’ll include the lessons that we might extract from what we know about how children learn.

You might find that at least some of this book feels a bit U.S.-centric. I know that this might rankle if you’re from another part of the world (which, hailing from Montreal, Canada, I am). That U.S.-centricity is just a function of a preponderance of available data as well as a cost and incentive structure around education that makes the American system an especially unsustainable leading indicator of changes that will come to the rest of the world. Put simply, while the price of education is particularly high in the United States, the opportunity cost of education is disproportionate to its value throughout the modern world.

Science fiction author William Ford Gibson famously said, “The future is already here, it’s just not evenly distributed.” As such, while everything I will share is researched and true, it is bound to be more true in some contexts and for some people than others. As such, it doesn’t matter whether the assertions that I make are absolutely true in all cases, but rather whether they are substantially more true than they were five or ten years ago, and whether they are likely to be even more true five or ten years from now. In other words, whether my arguments are directionally correct. Experience suggests that this is the case, and it follows that ignoring this perspective will lead to good money and time thrown after bad for all who consume education, and misdirected efforts and lost opportunities for those who seek to provide it.

So please read with an eye toward how these ideas might matter in your context, as opposed to why you might disagree. There’s a good chance that this book will challenge some things that you’ve believed strongly for a long time. Thanks in advance, and happy trails!