Fortitude: How the Tough Keep Going When the Going Gets Tough

Put a spark to a bit of gasoline in a small enclosed space, and the ensuing release of energy can propel a potato five hundred feet. Do the same thing hundreds of times per minute, harness that energy to propel a piston instead of a potato, and you get the propulsive power that can accelerate a Porsche 911 Turbo S to sixty miles per hour in less than three seconds.

This is the technology of internal combustion, which powers every non-electric car on the road today. Whether you ride in a leather-seated luxury vehicle like the aforementioned Porsche or a more modest vehicle sporting children’s car seats and a plethora of multi-colored stains creatively engineered by the occupants of those car seats (the story of my life) it’s incredible to think that the technology driving your family consists of hundreds of controlled explosions each minute, happening just a few feet away from where you sit.

It’s a robust and powerful technology, capable of great things, but it also can be surprisingly delicate. While the “sugar in the gas tank” thing is an urban legend (sugar doesn’t actually dissolve in gasoline), there’s an even simpler substance that would render an engine inoperable: water. Because water is heavier than gasoline, all it takes is a few cups of water poured into the fuel tank to float the gasoline and fill the fuel lines with water instead, leaving the engine a sputtering mess.

Our innate ability to learn is a lot like the technological marvel of the internal combustion engine, incredibly powerful and able to propel us great distances. But it also can be very fragile and easily disrupted.

That’s what happens to far too many students: They get water in their proverbial gas tank, and quit; 28 percent of college students drop out in their first year, and 57 percent aren’t done after six years in their so-called four-year program.169 Technological innovations seem to have made things worse, rather than better, with average MOOC completion rates in the high single or low double digits,170 and most online courses have drop-out rates as high as 87 percent.171

Why does this happen? This is a question that every educator needs to take seriously.

As head coach of the Green Bay Packers in the 1960s, Vince Lom- bardi won more championships than any of his NFL peers. He is famous for his declaration that, “Winners never quit, and quitters never win.”

Alas, life is sometimes more complex than football. A dogged refusal to quit is the sunk cost fallacy, throwing good money after bad and ignoring the opportunity cost of all the more productive and successful things that you could be doing. In fact, as Seth Godin tells us, winners quit things all the time; “they just quit the right stuff at the right time.”172

How do you know which is the right thing, and which is the right time? How do you distinguish projects that should rightfully be aban- doned from projects undergoing what Godin calls “the dip”—the discouraging and sometimes painful setbacks that are temporary, even if they might not look that way?

Without a crystal ball that can peer into various possible futures, we have to make our best guess, extrapolating from the experiences that we’ve had and the information that we’ve collected. This is easier said than done because as with the challenges of insight, we don’t actually make the best decisions we can with the information that we have, but rather with the inferences that we draw from the information that we have. Two people can have the same information but draw different inferences. Good inferences lead to good decisions, and bad inferences lead to bad ones.

The 3 Ps of Pessimism

Two people can have the same information but draw different inferences. Good inferences lead to good decisions, and bad inferences lead to bad ones.

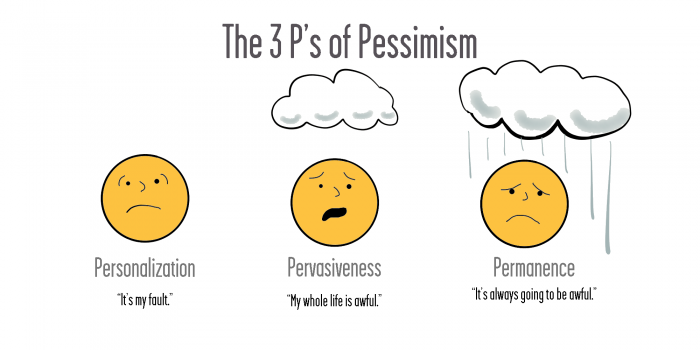

Two people can have the same information but draw different inferences. Good inferences lead to good decisions, and bad inferences lead to bad ones. Few people have researched the mental habits that lead to these sorts of inferences and decisions as deeply as Martin Seligman, an authority in the fields of resilience, grit, learned helplessness, optimism, and pessimism. Seligman has identified three patterns of bad inferences that can lead to especially bad decisions, such as quitting a challenge that you would be better off making the effort to complete. He calls them the three Ps of Pessimism: personalization, pervasiveness, and permanence.

- Personalization is the belief that we are at fault for whatever has gone wrong (“it’s my fault that this is awful”)—like attributing a poor grade to incompetence rather than lack of preparation.

- Pervasiveness is the belief that whatever has gone wrong will affect all areas of life (“my whole life is awful”)—like extrapolating a conflict with a co-worker into a belief that nobody likes you.

- Permanence is the belief that the aftershocks will last forever (“and it’s always going to be awful”)—like believing that losing your job (or quitting school!) will dictate the rest of your life.173

Learning is tough, especially if you’re trying to learn something that’s going to make a discernible impact on your life. You’re bound to run into challenges and setbacks along the way. While those challenges and setbacks are objective facts, different inferences can be drawn from them. If the student is struggling with a particular concept or exercise, for example, rather than inferring that more study and perhaps support are needed, the student personalizes the failure (“I’m too stupid to learn this”), sees it as pervasive (“I suck at school”), and expects it to be permanent (“I’m never going to be able to do this”).

While those challenges and setbacks are objective facts, different inferences can be drawn from them.

While those challenges and setbacks are objective facts, different inferences can be drawn from them. You might be tempted to wonder why so many people draw such flawed and damaging inferences from the setbacks that they experience. Perhaps there’s a better question that we could ask: Why is it that some people don’t?

In 1990, Jerry Sternin was sent by Save the Children to fight severe malnutrition in rural Vietnam. Sternin knew well the complex systemic causes of malnutrition, but he considered that knowledge to be TBU—“true but useless”—since changing something as broad and complex as national sanitation, poverty, or education was wholly impractical within the time frame and resources at his disposal.

Instead, he traveled to villages and met with the leading experts on feeding children: village mothers. He asked whether there were any poor families whose children were bigger and healthier than most, and he followed the “yes” answers to discover what the mothers of those children were doing: feeding their children smaller portions of food more often throughout the day, adding brine shrimp to their daily soup or rice dishes, and taking care to ladle from the bottom of the pot, where the shrimp and greens settled. Rather than trying to imagine a solution that doesn’t exist, Sternin found a solution that did and trained others to use it, and within six months, 65 percent of the children in the villages where he worked were better nourished.174

This approach of looking to replicate what works, rather than solve what doesn’t, is called “Finding the Bright Spots” in Chip and Dan Heath’s book Switch. As Dan explains in Fast Company:

Let’s say you launched a new sales process six months ago. So far, the results are mixed. Two reps have doubled their sales. Six are selling about what they were before. Two have slipped.

And three are threatening to quit if you don’t abandon the idea. What do you do? Well, most managers would put on their problem-solving hats and spend all their time dealing with the three bellyachers. Those two stars can take care of themselves, right? Well, no, you’ve got it backwards. You should be spending your time trying to clone what those top two are doing. How have they implemented the new process? Maybe they’ve created some new sales literature, or maybe they’ve tweaked the way they approach new leads. If you can get clear on what’s working for them, you can spread those answers to your other reps.175

Rather than asking why some people quit, the more constructive question to ask, even in situations where continuing forward seems impossible, is why do some people keep on going?

Sooner or later, all students will hit a rough patch. Maybe the subject matter is less interesting or more challenging than they first expected. Maybe they get confused by an assignment or earn a grade that isn’t up to their standards. Maybe they’re trying to fit this course into an already busy schedule, and they’re tired. Maybe there’s other life drama going on, fraying their nerves and attention. Even under the best of circumstances, some struggle is unavoidable. As we learned from K. Anders Ericsson, the only way we really learn and get good at something is through deliberate practice, which involves stepping outside your comfort zone and trying activities beyond your current abilities.176

Not everyone responds to these challenges in the same way. While some slow down or drop out, others thrive and continue to succeed. What’s different about those who succeed, even in the face of stress, trauma, and learning challenges?

Bright Spots of Learning

Gifted students are overrepresented in dropout statistics.

Gifted students are overrepresented in dropout statistics. Our first go-to assumption might be that they’re smarter, but that isn’t it. Gifted students are overrepresented in dropout statistics (statistically speaking they’re only about 2.5 percent or 3 percent of the general population,177 but 4.5 percent of those who drop out of high school).178 The same is true of discretionary adult education. Thousands of highly intelligent adults drop out of online courses every year. Intelligence alone won’t pull you through certain learning challenges.179

What’s different about those who succeed, it turns out, is that they possess certain non-cognitive capacities: motivation, perseverance, time management skills, work habits, and the ability to ask for feedback and support. These qualities make whatever intelligence we have useful and practical. It’s not enough to be brilliant and work on a problem for five minutes, then give up. It’s much better to be reasonably smart and keep trying new approaches after your first attempt stalls. If that isn’t enough, then go get help from an instructor or a coach, and come prepared with specific questions on how to move forward.

Grade point average in college isn’t predicted by intelligence.

Grade point average in college isn’t predicted by intelligence. Researchers have found that grade point average in college isn’t predicted by intelligence as measured by IQ tests or other standardized test scores. Instead, noncognitive academic skills, such as self-control and grit, are key to academic success. These are the skills that fall under the broad umbrella of Positive Psychology, developed by people such as Martin Seligman, who is considered the father of the Positive Psychology movement; his protégé, Angela Duckworth, who wrote the book about grit; Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, famous for his concept of flow; Carol Dweck, who brought us the Growth Mindset; and many others. As researchers from the University of Chicago Consortium on Chicago School Research explain:

The prevailing interpretation is that, in addition to measuring students’ content knowledge and core academic skills, grades also reflect the degree to which students have demonstrated a range of academic behaviors, attitudes, and strategies that are critical for success in school and in later life, including study skills, attendance, work habits, time management, help-seeking behaviors, metacognitive strategies, and social and academic problem-solving skills that allow students to successfully manage new environments and meet new academic and social demands. To this list of critical success factors, others have added students’ attitudes about learning, their beliefs about their own intelligence, their self-control and persistence, and the quality of their relationships with peers and adults.180

The skills of fortitude have a disproportionate impact on our ability to make the most of our good fortunes or transcend the challenges of our bad ones.

The skills of fortitude have a disproportionate impact on our ability to make the most of our good fortunes or transcend the challenges of our bad ones. Or, put more succinctly by economist James Heckman, “Much more than smarts is required for success in life. Motivation, sociability (the ability to work with others), the ability to focus on tasks, self-regulation, self-esteem, time preference, health, and mental health all matter.”181 Let’s call this aggregate set of skills fortitude for the sought-after and coveted quality that emerges from them. Fortitude is the hidden key to success, especially in our new world of volitional, online-first learning, where self-motivation and self-regulation are essential.

I’m not suggesting that that fortitude is the only thing that matters to a person’s success, educational or otherwise. There are a multitude of factors, including native intelligence, upbringing, socioeconomic status, and of course luck; and they all have some influence. What I am suggesting—and what the data support—is that the skills of fortitude have a disproportionate impact on our ability to make the most of our good fortunes or transcend the challenges of our bad ones.

High Adversity with High Support

Ideally, the seeds of the crucial noncognitive capacities of fortitude are sown in the formative experiences that we go through as children. The key is not to avoid stress or challenge, but rather to face it with support from those around you. This is the ultimate antidote to the inferences of personalization (“This is difficult stuff. Let’s try again.”), pervasiveness (“This is hard, but there are many things you’ve mastered and are doing well.”), and persistence (“Some things feel really hard, but eventually and with practice, things get better.”). As clinical psychologist Dr. Sherry Walling and her venture capitalist husband, Rob Walling, explain:

There is certainly a body of literature in the psychological research to support this pattern. High adversity with high support leads to perseverance, resilience, and grit. As children, these entrepreneurs learned the ability to encounter hard things without folding. They learned to press into their support systems, to find tools to help them move forward, to persevere even in the midst of difficult circumstances.182

What if you didn’t have that combination of challenges and support as a child? Fortitude is often treated as an unexamined aspect of character: Maybe you can develop it early in life, but past a certain point you either have it or don’t. But the data tell a different story, and the most exciting thing about the skills of fortitude is that they are so incredibly malleable. Which is not to say that we aren’t best served developing fortitude as children—of course we are. Just as in a perfect world we’d all have good parents, live in stable homes, and be well- provided for. These are important things to aim for as a society, but beyond the scope of what any individual educator can do. As teachers, we can’t change someone’s intelligence, nor can we change their upbringing or socioeconomic status, but we can teach the component skills of self-discipline, self-regulation, and grit that make up fortitude.

Can We Learn Fortitude? The Science Says Yes!

Basketball is a tall person’s game. Although there’s no technical height minimum for players, there have been only twenty-five players in NBA history with a listed height under 5’10,” and only four who were active since 2010.183 If you stand a modest 5’7” (like me), then it doesn’t matter how much you like basketball, you should probably look elsewhere for a successful career path. In the words of legendary entrepreneur and investor Bill Campbell, “You can’t coach height.”

“You can’t coach height.”

“You can’t coach height.” By the same token, Nobel laureates need to be on the top extreme of the intelligence curve, Seal Team Six requires the best in physical fitness, and the highest political offices require remarkable charisma and ability to influence. When we think about elite performers, we tend to focus on these essential traits of the remarkable few who make the headlines. Yet this attention to world-class performers leads us astray when it comes to education and learning, because it focuses too heavily on traits and not enough on skill. World-class performance requires a combination of both; the trait of height (and coordination) combined with the skill developed by ten thousand hours of focused, deliberate practice.

We all can learn and grow by focusing on our noncognitive capacities of motivation, perseverance, time management skills, work habits, and the ability to ask for feedback and support.

We all can learn and grow by focusing on our noncognitive capacities of motivation, perseverance, time management skills, work habits, and the ability to ask for feedback and support. The research that has shown us how malleable the various components of fortitude can be to interventions is proof that, contrary to what many believe, fortitude is not a trait, or a virtue, as Aristotle called it so long ago. It is a skill, and skills can be developed. Although most of us will never play in the NBA, we all can significantly improve our fitness, health, and enjoyment of sports, and to do that, we must focus on the environment in which we learn about physical activity, the mindset we adopt, and the lifelong habits we’re forming. By the same token, we all can learn and grow by focusing on our noncognitive capacities of motivation perseverance, time management skills, work habits, and the ability to ask for feedback and support.

Fortitude is not only something that can be taught, but also something that modern educators must teach. These are the critical skills of success in the modern world, and without them, many of our students can’t even complete the training that we currently provide. It is incumbent on all educators to provide whatever fortitude training is necessary for their students to complete their learning and reap the promised results.

The prospect of supporting people to develop these crucial skills is exciting, but how do we do it? We can hope that people stumble into circumstances that provide high adversity with high support, or we can carefully engineer these circumstances for our learners and provide the tools to make them successful.

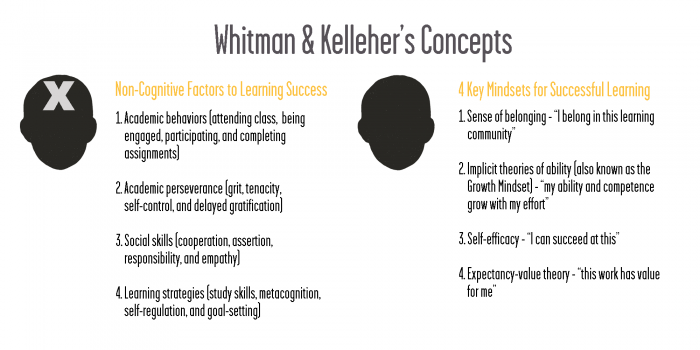

We can lean on a good deal of research that has been done into what key skills are most important for educators to impart. In their book Neuroteach, Glenn Whitman and Ian Kelleher lay out the key noncognitive factors that have been linked to learning success, as well as the key mindsets that contribute to academic performance. The noncognitive factors are academic behaviors (attending class, being engaged, participating, and completing assignments); academic perseverance (grit, tenacity, self-control, and delayed gratification); social skills (cooperation, assertion, responsibility, and empathy); and learning strategies (study skills, metacognition, self-regulation, and goal-setting). The four key mindsets are a sense of belonging (“I belong in this learning community”); implicit theories of ability (“my ability and competence grow with my effort,” also known as the Growth Mindset); self-efficacy (“I can succeed at this”); and expectancy-value theory (“this work has value for me”).184

It is admittedly a long list, but as educators, we can work with this. Essentially, there are four things that our students need us to do in order to support them in developing fortitude:

- Support successful behaviors. Foster engagement; be creative in encouraging participants to attend live classes and participate in online discussions; provide incentives and support for completing assignments.

- Provide scaffolding for perseverance. It’s not enough to just tell students, “You need to keep trying!” We must seek to develop creative ways to help students understand the kind of challenges they will face, and to persist through those challenges even when it doesn’t feel immediately rewarding for them.

- Create opportunities for cooperation and taking initiative. Education feels most difficult when one has the sense of being isolated and alone in a course. When there are opportunities to cooperate with others, take initiative to help others, and become part of a tribe (even a virtual one). Learning becomes more meaningful and more fun. As a side benefit, participants can sharpen their social skills along the way.

- Help learners understand and develop their own learning strategies. It’s possible to become an expert in the process of learning itself. The best students do so well in part because they have mastered their own learning strategies. They are self-aware about when they understand a concept and are able to take action on it. They set personal goals and track their progress toward those goals. For others who haven’t mastered these approaches on their own, we can help coach them toward more effective learning.

An important key here is to figure out how to share those tools so that people not only understand them, but also adopt and use them. This is the teaching about vs. teaching to challenge again. The best tools won’t do any good if students learn about them but fail to make any changes in their behavior. The good news is that we aren’t flying blind here. There’s a massive research base from the fields of positive psychology and neuroscience to draw upon. We can cherry-pick the best research-proven techniques, try them with our own students, and tweak them over time.

The good news comes with the important caveat that these non- cognitive capacities are highly individual, which means that the way you help others develop these capacities will depend on both your unique style and theirs. A hard-charging fitness coach approach of “tough love, no excuses!” may instill persistence with its in-your-face challenges, but that won’t work with every student. By the same token, an intuitive and energetic approach of spiritual healing may support positive growth, but again, it won’t work with every student. We must lean on our strengths and at the same time be adaptive and malleable to our students’ needs.

So now let’s get more actionable, and break out four specific approaches to developing these sorts of skills. Each is backed by research, and each is something you can integrate in direct, practical ways.

Start with Motivation

It all begins with motivation. If learners aren’t motivated, there’s no tool or hack that can make a difference for them. They’ll just give up when the going gets tough. As we’ve seen, though, not everyone gives up. Some people keep on going, most especially those possessed with Angela Duckworth’s quality of grit. But as Caroline Adams Miller explains, there’s no such thing as being “gritty” about everything. Grit is specific to the things that we care about.185 But where does that grit come from? Where do we find that motivation to keep on going, even though the going is tough?

Research into self-determination theory has demonstrated the importance of having intrinsic motivation: doing something because it is interesting and enjoyable, or at least an expression of one’s values and identity, rather than doing it because one feels compelled by external forces. Intrinsically motivated people try harder and longer, perform more flexibly and creatively, and learn more deeply than extrinsically motivated people.186

What may come as a surprise is that intrinsic motivation can be undermined by extrinsic demands, such as rewards, prizes, grades, and social pressures. In a traditional academic setting, this means that incentive systems such as grades and rewards can lead students to lose sight of their own intrinsic motivations.187 When this happens, they can begin working only for the extrinsic rewards, and the benefits of intrinsic motivation (persistence, flexibility, creativity, and deep learning) fade away.

Help Learners Develop Self-discipline

The second approach is to help learners develop self-discipline, but not in the way you might think. Discipline is often confused with self-denial, such as undertaking an unpleasant cleanse diet or forcing yourself to work harder and longer. In fact, discipline is about the presence of mind to choose what you actually want over what you might feel like in the moment. The path to making self-disciplined choices is through practices of mindfulness and gratitude, which open us up to more and larger perspectives.

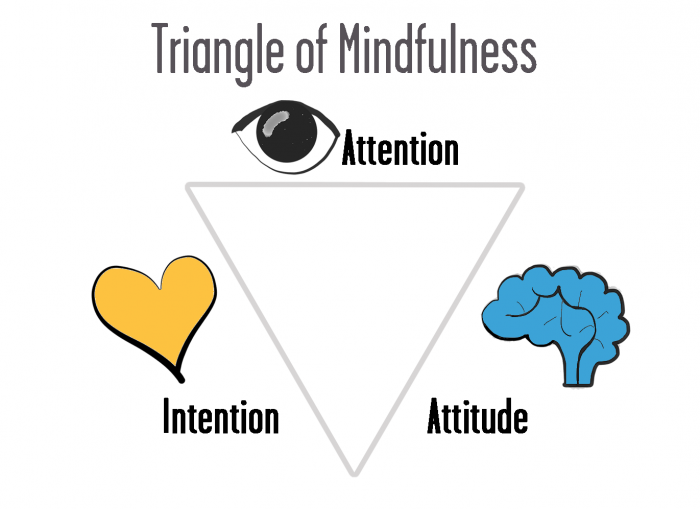

Mindfulness has become an incredibly hot topic in recent years, so you’ve probably heard that mindfulness practices have been demonstrated to decrease depression, anxiety, and diverse stress-related disorders. More important for education, mindfulness can increase self-efficacy, which is a key contributor to learning. But exactly what is mindfulness?

Mindfulness is often described as a type of awareness: a way of relating to all experience—positive, negative, and neutral—in an open and receptive way. This awareness involves freedom from grasping and from wanting anything to be different. It simply knows and accepts what is here, right now. This mindfulness involves knowing what is arising as it arises, without adding anything to it, trying to get more of what we want (pleasure, security), or pushing away what we do not want (fear, shame).

Psychologists Shauna Shapiro and Linda Carlson have developed a model of mindfulness comprising three core elements: intention, attention, and attitude. Intention refers to knowing why we are practicing mindfulness, and understanding our personal vision and motivation. Attention involves observing the operations of one’s moment-to-moment, internal and external experience. And attitude refers to the qualities one brings to attention, and includes a general sense of openness, acceptance, curiosity, and kindness.188

A mindful learner is able to relate openly and flexibly to the diversity of experiences that come with learning new skills—taking in stride whatever problems, challenges, or feelings of “stuckness” arise. When faced with distractions, they think clearly about what really matters and what must be set aside.

Teach Mental Contrasting

Once learners are focused and moving forward, they’ll learn enough to start taking on more difficult challenges, which will lead to setbacks and temporary failures. Specific strategies can begin to help them cope with the up-and-down nature of learning progress. One powerful strategy is called mental contrasting, essentially preparing people for challenges before they occur.

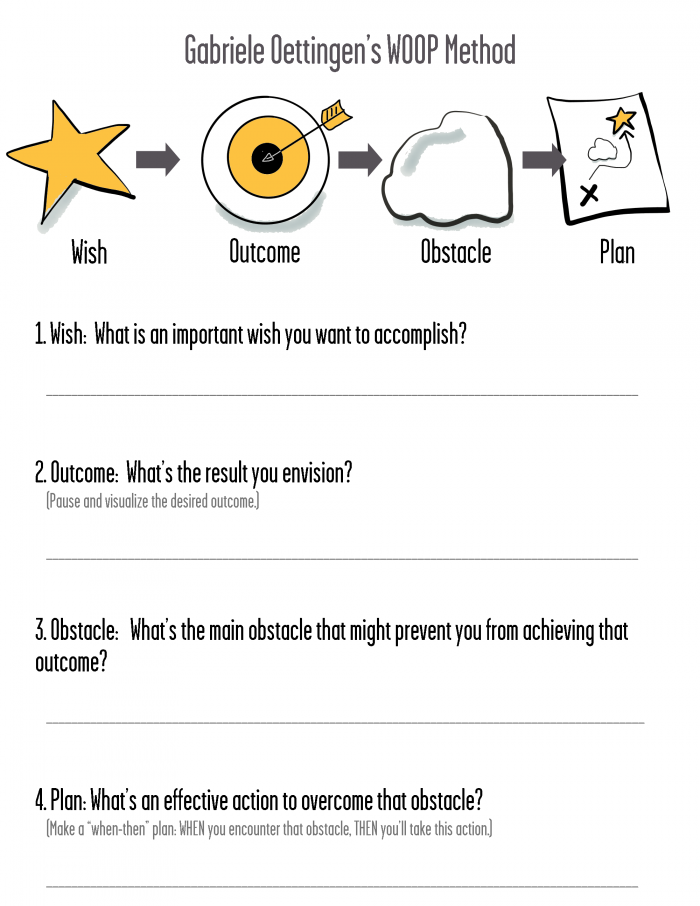

This concept comes from Gabriele Oettingen, a leading psychologist at New York University. She explains in her book Rethinking Positive Thinking that both optimists and pessimists have consistent flaws in their thinking, which lead to subpar performance when faced with setbacks. Optimists are all about “indulging.” They fantasize about the amazing future they are going to have and how good they’ll feel when they learn everything in their course. This feels great at the time, but doesn’t lead to achievement, because everything comes crashing down after the first significant problem crops up.

Pessimists instead get stuck in “dwelling.” They think about all the barriers to their learning and why they won’t be able to achieve their goals. For example, a pessimist in a watercolor class might dwell on how her paintings never turn out the way she hopes, how she doesn’t have anything interesting in her yard to paint, and so on. You probably won’t be shocked to learn that pessimistic dwelling doesn’t lead to successful learning, either.

Mental contrasting is a clever alternative to both types of flawed thinking. The trick is to concentrate on a positive outcome and simultaneously to imagine potential obstacles on the path to success. Oettingen teaches the easy-to-remember mnemonic WOOP for the steps in doing this:

- Wish. What is an important wish that you want to accomplish? Your wish should be challenging but feasible.

- Outcome. What’s the result you envision? Really pause and take a little time to visualize the desired outcome.

- Obstacle. What’s the main obstacle that might prevent you from achieving that outcome?

- Plan. What’s an effective action to overcome that obstacle? Make a “when-then” plan; WHEN you encounter that obstacle, THEN you’ll take this action.189

Cultivate a Growth Mindset

Struggle, challenge, and difficulty are enormously beneficial for learning, long-term memory, and skill development, even though intuitively, we feel as if we’re failing and falling behind. It feels great to absorb a new idea presented in an interesting way or to “check the box” of completing a relatively easy task. However, it feels deeply uncomfortable to work on a project and not achieve the desired outcome, or to submit an assignment and receive critical feedback.

The best teachers find ways to support people through this uncomfortable curve of growth. Specifically, according to Whitman and Kelleher, teachers should help students develop an iterative process of trying strategies, evaluating progress, and then refining or finding new ones. We should coach our learners to deal positively with failure, seek out challenges, and value mastery goals rather than performance goals.

Each of the previous strategies contributes here as well. Motivation is essential; self-discipline enables taking thoughtful and constructive action after a setback; and mental contrasting puts plans in place to deal with challenges before they occur.

To go further, we can combine these strategies with encouraging our learners to develop a growth mindset. Around ninth grade, most people begin to shift from a growth mindset to a fixed mindset. This means they begin to think of their intelligence and other abilities as fixed traits that they are born with and must accept. They become increasingly afraid to take intellectual risks or make mistakes for fear of hurting their grades.

A fixed mindset is anathema to learning and development. The most successful students aren’t afraid to take risks or fail when learning.

They trust in themselves to learn from each mistake and get better in the process. One of the most effective things we can do for all our students is to help them adopt this constructive, creative mindset.

So now we’ve explored the three components of Leveraged Learning: knowledge, insight, and fortitude. We’ve dug into each of them in turn, and what it takes to build them into a learning experience that leads to the success that all educators owe to their students. Now let’s turn our attention to the last piece of the puzzle, which is the process of building actual learning experiences.

Want to test your understanding of the ideas that we just covered? Or start conversations with interested friends and colleagues? Here are a few questions to guide you:

1. What are the 3 Ps of Pessimism?

2. Even gifted students and intelligent adults drop out of school. What’s different about those who do succeed?

3. What are the skills that make up fortitude?

4. According to the book, Neuroteach, what are the key non- cognitive factors that have been linked to learning success?

5. What are the four key mindsets that contribute to academic performance?

6. What four things do students need educators to do for them?

7. What research-backed approaches can educators apply to help people learn and develop?

8. What kind of motivation is the right kind for learning—intrinsic or extrinsic motivation? Why?

9. How can external rewards undermine intrinsic motivation and, ultimately, learning?

10. If self-discipline is not self-denial, then what is it?

11. What practices help people make self-disciplined choices?

12. According to Shapiro and Carlson, what are the three core elements of mindfulness?

13. What is mental contrasting?

14. Describe the steps in Gabriele Oettingen’s WOOP method.

15. What is a growth mindset as opposed to a fixed mindset? Which one is better for learning?

Like What You Read, and Want to Go Deeper?

Here are a few good books to take a look at if you’d like to go deeper on some of the ideas presented in this chapter.

- Martin Seligman’s Flourish

- Angela Duckworth’s Grit

- Carol Dweck’s Mindset

- Paul Tough’s How Children Succeed