Knowledge: Making it Easy for People to Learn

Just how quickly can you learn skills such as surfing, professional poker, Brazilian jujitsu, parkour, or foreign languages? The education system needs to teach in the most effective ways. It needs to use what science has taught us about how people learn to engage learners in rapid skill development. Lectures have long been known as a poor way to bring people up to speed. But what works instead? To find out, let’s look at how people learn.

There’s a subculture of meta-learning and rapid skill acquisition dedicated to answering these questions, popularized by Timothy Ferriss in his 4-Hour book series, podcast, and television show. Connor Grooms is one of those rapid learning aficionados. After running several thirty-day experiments with goals including learning web design, making films, and even putting on twenty-six pounds of muscle, Grooms turned his attention to learning Spanish. He not only learned to speak Spanish, but also made a documentary about the process.120 Grooms worked hard to get so good so quickly, investing five hours a day for thirty days while maintaining his full-time work. Writing for Forbes, Jared Kleinert explained Grooms’ process:

His success lies in finding the learning methods that work best from a data-driven approach, whether traditional (like flashcards) or unconventional (like a mimicking method he follows in the documentary to learn proper pronunciation). Nothing Grooms does is absurd. He’s simply willing to take advice from dozens of books, world-class mentors like Benny Lewis when it comes to language-learning, and then actually put in the work.121

This rapid learning experiment formed the basis of what eventually became BaseLang, Grooms’ Spanish tutoring company, which Kleinert described as “the closest thing to immersion you can get without moving to a Spanish-speaking country.” Not one to rest on his laurels, Grooms decided to raise the ante on how quickly languages can be learned. He enlisted the help of Tony Marsh, a language teacher whose clients include the U.S. Navy and NATO, to learn Portuguese in just a week.122

The key to real value is in the ability to do great things with your knowledge.

The key to real value is in the ability to do great things with your knowledge. Here’s the thing about learning a language, whether it’s Spanish, Portuguese, or anything else: fluency alone doesn’t qualify you to do all that much. On the other hand, the lack of fluency can disqualify you from a whole lot! The same is true of most knowledge and skills, unless they’re highly specialized, or you reach a top-tier level of proficiency. For example, a basic fluency in the skill of cooking might qualify you to prepare dinner for your family, but to work in the field you’ll have to kick things up several notches. The same goes for everything from management to martial arts. A basic conceptual fluency doesn’t actually get you all that far. The key to real value is in the ability to do great things with your knowledge.

With that said, we do still need the knowledge. It isn’t the be all and end all, but it is the foundation for any success that we care to achieve. So it makes sense for us to follow Grooms’ lead and acquire the knowledge that we need as quickly and efficiently as possible, in order to move on to bigger and better things. Entire excellent books have been written on this field, and I couldn’t hope to give it an exhaustive treatment in a single chapter. What follows is the bare minimum that you need to know and understand in order to do this well, starting with why learning and memory are so hard.

To understand how we might accelerate the learning process in this way, let’s turn our attention to memory, which is the base building unit of learning.

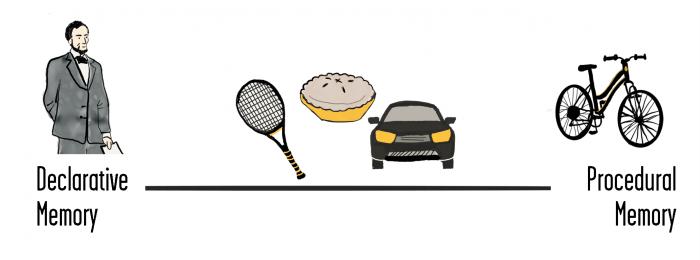

Imagine a spectrum of all the things you might learn. On one end you’ll find something like remembering your phone number or reciting the Gettysburg Address—that’s knowledge acquisition, pure and simple, with no skill involved. Learning professionals call this declarative memory, which is the “knowing what” of vocabulary, theories, dates, facts, and figures. On the other end is something like tying your shoelace or riding a bicycle. That’s pure skill, and there’s really no informational knowledge required. This is called procedural memory, which is the “knowing how” to do things, generally involving motor skills. Of course, there are lots of things that sit somewhere in the middle and call on both types of memory, like playing tennis, driving a car, negotiating a deal, baking an apple pie, or preparing a budget.123

All of these things are based on remembering and repeating (either in words or in actions) the things that we’ve been told and shown. That sounds easy, but it isn’t. It turns out that remembering is surprisingly hard.

Our Brains Are Designed to Forget

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes is more than the epitome of deductive brilliance, he also presents a fascinating insight into how we all think and how we might think better. One of Holmes’ famous eccentricities was a deep and thorough knowledge of some areas, and a striking lack of knowledge of others. When taken to task for this by his sidekick, Dr. John Watson, in A Study in Scarlet, Holmes explains, “I consider that a man’s brain originally is like a little empty attic, and you have to stock it with such furniture as you choose.”124 Essentially, Holmes is saying that he’s careful to not learn certain things, in order to make room for the things that he deems truly important to know.

The challenge of retention isn’t a bug, it’s a feature, albeit a sometimes annoying one.

The challenge of retention isn’t a bug, it’s a feature, albeit a sometimes annoying one. While Holmes may be extreme, he is far from unique. We are all exposed to far more information than we can notice or retain, and our brains aren’t designed to remember everything that we’ve ever learned. In fact, they’re designed to retain only what they actually need, which means that memories evaporate entirely over time if not used. So when we forget huge chunks of things that we used to know, it isn’t necessarily evidence of laziness or attention deficits, but rather a sign that our brains are working exactly as they should.125 In other words, the challenge of retention isn’t a bug, it’s a feature, albeit a sometimes annoying one.

How do our brains decide whether knowledge or skill is worthy of being remembered? There are a few criteria, the first of which is whether we understand it in the first place.

Scaffolding Ideas on Top of Ideas

Computers can run millions of calculations in a matter of moments, but they can’t actually think, or know, or understand. That’s a good thing if you’re looking to program them to do something new: You don’t have to explain why it makes sense or think about tying your idea to their existing knowledge base. You just write the software, and the computer runs it. Easy peasy. With human beings, it’s decidedly more complicated. Our brains aren’t designed to assimilate information and ideas completely unrelated to our context or frame of reference. Anything we learn or are exposed to must fit somewhere in the hierarchy of the things that we already know and understand.

That’s why so much of the art of teaching and explaining is finding the metaphors and telling the stories that help students connect new ideas to things that they already know. Learning professionals call this scaffolding—building one idea on top of another—and it’s why this book is laden with stories and vignettes. Hopefully, they help you get your head around the ideas I’m presenting and entertain you along the way.

Lack of scaffolding is one of the biggest reasons why learning breaks down.

Lack of scaffolding is one of the biggest reasons why learning breaks down. The lack of scaffolding is one of the biggest reasons why learning breaks down, and conversely it is the reason why some remediation programs have impressive results. Consider, for example, reading interventions for children who are severely below grade level, which can effectively advance participants by several grade levels in a few months.126 They’re great programs, but they beg the question of why we couldn’t have applied them to all the kids in the class to begin with and saved them years of study. The answer is that in many cases, remediation works not only because of the extra attention and excellent pedagogy, but also because in the years between the original learning attempts and remediation, the necessary scaffolding of supporting concepts and ideas was built.

Note also that scaffolding can sometimes be a function of development and maturity, in addition to prior learning. In other words, some things (like quantum physics) are hard no matter how old or smart you are. But other things (like basic addition) are hard up until a certain developmental maturity has been reached, and then they become easy. This is one of the challenges for people possessing what Todd Rose calls “jagged learning profiles”—stronger in some areas and weaker in others.

We’re all some configuration of jagged, and expecting us all to progress at the same pace in all areas makes very little sense.

Without scaffolding, it’s hard to make sense of what you’re learning, and rule number one of memory is that if we don’t understand it, we don’t remember it. And rule number two? That has to do with how relevant the information is to you.

Inferring Relevance from the Cone of Experience

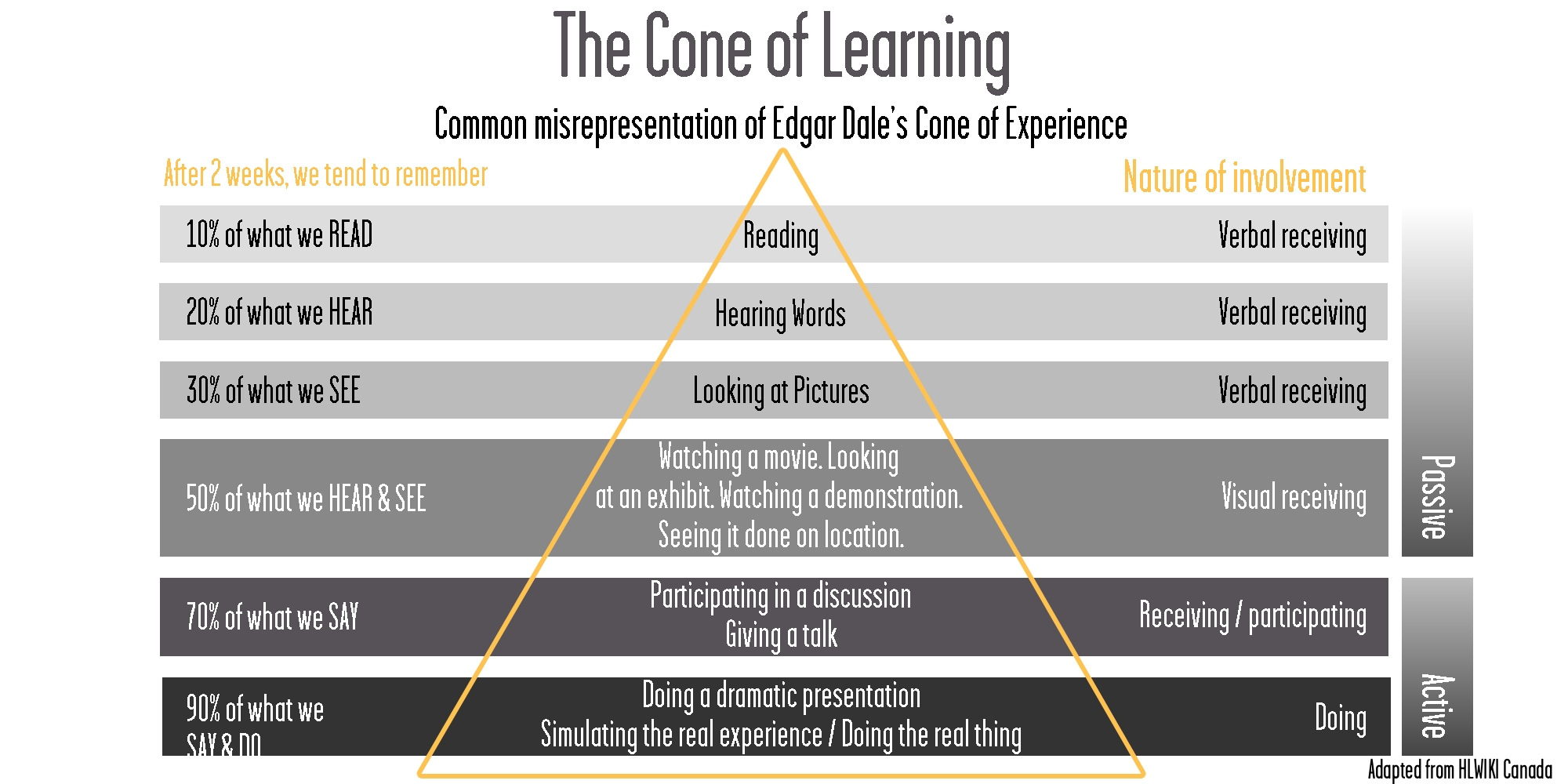

Born in 1900 in Minnesota, Edgar Dale showed passion for effective education ranging from vocabulary to readability to his doctoral thesis, titled Factual Basis for Curriculum Revision in Arithmetic with Special Reference to Children’s Understanding of Business Terms. At the age of 46, Dale developed a concept called the Cone of Experience in a textbook on audiovisual methods in teaching.127

That model has been widely misrepresented as the Cone of Learning, which purports to say how much people remember based on how information is presented to them (from 10 percent of what we read and 20 percent of what we hear, to 70 percent of what we say and write, and 90 percent of what we do). Now, this is layer upon layer of bad science. Dale’s original Cone of Experience was not based on scientific research, and he even warned his readers not to take it too seriously. And the retention percentages weren’t even part of his original diagram. They were added later on.

Treating this model as gospel would be an egregious overreaching, as would giving any weight to the specific numbers on the diagram. But even though the model is sorely lacking in factual accuracy, it is directionally correct and useful. It intuitively makes sense to us that we would better remember something that we actually did than something that we read in passing in a book.

Memories are linked to the environment, experience, and state of mind in which they were formed.

Memories are linked to the environment, experience, and state of mind in which they were formed. This is for two reasons: The first is that learning is associative. In other words, memories are linked to the environment, experience, and state of mind in which they were formed. There is ample research showing that this is true, ranging from divers who memorized words while underwater and were better able to recall those words underwater than on land, students who memorized words while jazz music was playing and were better able to remember them with jazz music than without, and bipolar patients who best remembered things they experienced during manic phases when they were again in manic phases, and likewise for depressive phases.128

The second reason is pragmatic. We remember what our brains think is relevant to us, and the more involved we are with the experience (doing, discussing, and writing, as opposed to reading, hearing, and seeing), the more likely it is to be relevant to us.

So far our whirlwind tour of how we learn and form memories has taken us through the two types of memory, our natural tendencies to forget, scaffolding concepts on top of others, and the need for learning experiences that tell our brains the material is relevant to us. We’ll explore how to design all this into a learning experience soon. But first, there’s one more important factor to consider, which is that often even if we do remember, it doesn’t mean we’ve really learned what we were hoping to learn.

“Wax on, wax off” has become a cultural catchphrase, synonymous with karate instruction, learning by doing, and the movie that started it all. The original 1984 Karate Kid tells the tale of Daniel LaRusso, a scrawny kid from New Jersey who moves to Southern California. He runs afoul of a group of boys who study a predatory brand of karate called Cobra Kai, whose motto is “Strike first, strike hard, no mercy.” LaRusso meets Mr. Miyagi, a wise old man who teaches the boy his own brand of karate, which emphasizes self-defense and inner balance.

The training follows a non-traditional approach. While his Cobra Kai rivals practice punching and kicking in their dojo, Mr. Miyagi demands obedience from LaRusso with no questions asked and sets him to perform tasks such as sanding the floor, painting the fence, and waxing his cars (the iconic “wax on, wax off”). Finally LaRusso’s patience with seemingly pointless manual labor wears thin, and he challenges Miyagi to stop wasting his time. In the scene where it all comes to a head, Miyagi unleashes a flurry of punches and kicks that LaRusso surprises himself by blocking, using the movements he had practiced for sanding the floor, painting the fence, and so on.

It’s one of the movie’s classic moments, marking the start of LaRusso’s transformation from a wimpy, anxious kid to a competent, capable karateka who has found his center. There’s just one problem with the whole story: In real life, it never would have worked.

The idea of extrapolating the ability to block a punch from the experience of waxing a car is an example of what learning professionals call far transfer (as opposed to near transfer, which might be the ability to wax other cars or maybe boats). Far transfer, the ability to apply relevant learning to unfamiliar situations, is the holy grail of education. As Howard Gardner, the developmental psychologist behind the theory of multiple intelligences, writes, “An individual understands a concept, skill, theory, or domain of knowledge to the extent that he or she can apply it appropriately in a new situation.”129

To achieve far transfer, we must not only teach the relevant underlying principles, but also help students see how they apply in a wide range of circumstances.

To achieve far transfer, we must not only teach the relevant underlying principles, but also help students see how they apply in a wide range of circumstances. This is easier said than done. To achieve far transfer, we must not only teach the relevant underlying principles, but also help students see how they apply in a wide range of circumstances.130 This doesn’t happen automagically, as Karate Kid suggests. Joseph Aoun, president of Northeastern University in Boston, explains this further:

Studies have shown that students rarely exhibit the ability to apply relevant learning to unfamiliar situations. They may find themselves overly dependent on familiar contexts and inflexible to new applications. They also may lack a deep understanding of their domain, knowing the what but not the why. This blinds them from seeing how their knowledge could be utilized in a different setting.131

How can we engineer learning that is effective and efficient, that creates useful far transfer, and that sticks? It’s a tall order, but thankfully there are some shortcuts to get there.

First, Build Your Scaffolding

Imagine that you have to change a light bulb, but you can’t reach the fixture in the ceiling. The smart thing to do is get a ladder, but maybe the ladder is behind a small mountain of knickknacks in the garage, or maybe you don’t have a ladder and must trek across town to get one. So you place a barstool under the fixture and a chair on top of the bar stool. Because the fixture is still just out of reach, you grab a pair of salad tongs for the extra few inches. Armed with the salad tongs, you carefully climb on the chair that teeters atop the barstool and slowly reach up with the salad tongs, praying that you can maintain your balance long enough to accomplish the task before the whole thing comes tumbling down.

It sounds absurd, but this is precisely what far too many instructors attempt with their students and why so much learning never happens. Before designing a curriculum, instructors must ask themselves what knowledge and skill are prerequisites to the learning and whether it is realistic to expect the entire student base to be prepared. If the answer is no, the prerequisites must be built into the learning process. Minerva Schools at KGI, for example, offer a unique scaffolded program that progresses from being almost completely structured in the first year, to being almost completely driven by the students themselves in the fourth year.132 This is designed to give students the skills that they need to successfully tackle the later material.

There are many ways to do this effectively. Take, for example, the concept of a “memory palace.”133 The idea is to create imaginary locations in your mind where you can store mnemonic images. The most common type of memory palace involves making a journey through a place you know well, like a building or town. Along that journey there are specific locations that you always visit in the same order. This is literally a process of building visual imagery as scaffolding to support learning, in a context where you don’t have other scaffolding to hook new ideas onto. Another common practice is priming new learning by explaining how and why it will be used. This creates meaning that connects new learning to existing context, which all comes down to scaffolding.

Abstract concepts especially require scaffolding. Our brains aren’t wired to think abstractly, and our workaround involves analogies and metaphors. Einstein, for example, postulated his theories of physics by imagining the relative speed of a man walking on a moving train. Similarly, when we think of a timeline, we tend to imagine them in a visual order. These are metaphors that allow us to think about things our brains weren’t wired to think about.

So scaffolding is key, but it’s only the first of two. With solid scaffolding firmly in place, you’re ready to encode the new knowledge or skill.

Second, Encode Better

This starts by giving yourself the time that you need in order to learn. Spaced repetition over time is far more effective than one long cramming session (a good analogy is the difference between watering your lawn for ten hours straight on one day, versus for twenty minutes every other day for a month). Research supporting this goes as far back as Hermann Ebbinghaus’ “Forgetting Curve” in the 1880s, to Harry Bahrick’s research a hundred years later, and many other studies.134

The best sort of repetition is what K. Anders Ericsson calls deliberate practice, working purposefully and systematically on the things that are most important and challenging.135 This is the opposite of mindlessly reviewing notes, re-watching lecture recordings, or even practicing a single specific part of the skill you’re trying to master (practicing free throws for an hour won’t make you much better at basketball). Rather, you focus your attention on the things that are challenging for you to give yourself the best opportunity to learn and improve.

Finally, you must validate whether you really understand something or have just gone over the notes enough times to feel the illusion of fluency.136 This is done by creating a real-time feedback loop that can let you know whether you’re on the right track, and where you need to improve. This can be as involved as an instructor-led process of evaluation and feedback, as complex as using elaborate technology to provide real-time jolts or vibrations in a process of passive haptic learning,137 or as simple as self-testing using a free flashcard app that uses a process of spaced repetition138 like Anki. The key is to have a reliable feedback loop that tells you how you’re doing.

As much as possible, simulate the environment in which you’ll need to remember, ranging from where you study, to what you hear, and even how you feel. The Tony Marsh Method that Connor Grooms employed to learn Portuguese in a week, for example, involves spending as little time as possible in a classroom, and as much time as possible talking to native speakers. And Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield recounts in An Astronaut’s Guide to Life on Earth that the final stages of astronaut training involve running through all their procedures while sitting in the cockpit of the spacecraft. This is done so as to encode the memory as closely as possible to the environment in which it will be retrieved.

If you can’t predict exactly how or when you’ll need to perform, practice in different contexts and settings, so that the knowledge is encoded more thoroughly in your mind.

These may sound like simple ideas, but they can be powerful and yield spectacular results, as we’ve seen with examples ranging from remedial education, to rapid language acquisition systems like DuoLingo and Connor Groom’s experiments to learn Portuguese in a week. Done correctly, much of the process of learning and remembering knowledge and skill can be cut short. That means you’ll have more time left over for the more important work of developing insight.

Want to test your understanding of the ideas that we just covered? Or start conversations with interested friends and colleagues? Here are a few questions to guide you:

1. What is the real value in acquiring knowledge?

2. Why is it so hard for humans to remember everything we’ve ever learned?

3. What is declarative memory?

4. What is procedural memory?

5. What is scaffolding and how does it make learning easier?

6. Even though Edgar Dale’s Cone of Experience/Learning sorely lacks factual accuracy, what does it tell us about learning?

7. What does it mean to say that memory is associative?

8. The ability to apply learning is classified as either near transfer or far transfer. How are they different from each other?

9. Spaced repetition over time is an effective way to encode learning, and the best kind of repetition that leads to effective learning is deliberate practice. What does “deliberate practice” mean?

10. Why is a real-time feedback loop important in learning? Give examples.

Like What You Read, and Want to Go Deeper?

Here are a few good books to take a look at if you’d like to go deeper on some of the ideas presented in this chapter.

- Benedict Carey’s How We Learn

- Glenn Whitman & Ian Kelleher’s Neuroteach

- Brown, Roediger, and McDaniel’s Make It Stick

- John Hattie and Gregory Yates’ Visible Learning

- Joshua Foer’s Moonwalking With Einstein