Learning from the Experts

Science fiction fans in the early 1970s had slim pickings. There were some movies, novels, and three seasons of the original Star Trek. The first San Diego Comic-Con was held in August 1970, with roughly 300 attendees flocking to hear guests like Ray Bradbury, Jack Kirby, and A. E. van Vogt.

Fast forward a few decades, and sci-fi fans are blessed with a cornucopia of choices, including Star Trek franchise spinoffs; Star Wars sequels and prequels; the Marvel Comic and Harry Potter universes; movie series like The Matrix and Terminator; television shows like The Twilight Zone, The X-Files, Doctor Who, and Battlestar Galactica; movies that turned into television shows like Stargate; and even aborted cult series like Firefly and Netflix’s recent Sense8. And it’s not only about choosing media, but also about choosing sides, with rivalries like Star Trek vs. Star Wars, or Deep Space Nine vs. Babylon 5, and X-Men vs. The Avengers. There’s even Galaxy Quest, a parody of the tropes turning up in all the rest. Not to mention Comic-Con, the annual conference attended by over a hundred thousand fans. Far from consolidating, this industry has exploded into smithereens!

This is instructive, because we see the same pattern in the world of education; just as some parts of industry consolidate, others are breaking apart. Let’s explore what leads to this fragmentation, and what it means for education.

Sometimes industries don’t consolidate. In fact, sometimes they break into more and more pieces. Let’s return to the media landscape that we looked at in the last chapter. It is an interesting study in contrasts. At the same time as fifty media companies agglomerated into just six, the choice among just three television networks (ABC, CBS, and NBC) expanded to an average of one hundred eighty-nine channels available and seventeen watched in the average American home in 2014,113 not to mention all the programming that is available on Netflix, Hulu, and YouTube!

The classic example of this pattern of fragmentation is the book industry. In the days of Abraham Lincoln, one was lucky to have the opportunity to read a few dozen books in a lifetime, and the total of books available was numbered in the thousands or tens of thousands. The pace of book production grew to almost ten thousand new books per year in the early 1900s, and it continued to climb as high as three million new books per year in 2010.114 Of course, these numbers are cumulative; in 2010 Google reported almost one hundred thirty million books in existence,115 of which fifteen thousand were about Lincoln!116

Multiple (Non-Exclusive) Ways to Win

The first thing required for fragmentation to happen is more than one way to win. This is sometimes a function of utility; when it comes to pounding a nail into the wall, a hammer is a hammer is a hammer. The same isn’t true of screwdrivers, though: There are flat heads, Phillips heads, the rarer square head, and the Torx head, which is shaped like a six-pointed star. More often, though, fragmentation is a function of taste. While there’s just one way to hammer a nail, there are infinite ways to write a novel, compose a song, plan a great vacation, or prepare tomato sauce, which is why your local grocery store offers an array of flavors like sweet basil marinara, sun-dried tomato, Florentine spinach and cheese, tomato and pesto, tomato Alfredo, and many more.

In other words, we’re looking for situations where one choice doesn’t exclude you (or somebody else) from also making another. This is true in industries like music, where listening to one song or artist doesn’t preclude people from listening to many others; fashion, where I can own many different shirts from many brands, and so can you; tourism, as vacationing in London doesn’t preclude us from also vacationing in Cancun; apps, since installing Waze on my phone doesn’t preclude me from also installing Slack, Spotify, or Angry Birds; and even cars, as I may not be in the market for more than one, but my driving a Toyota doesn’t preclude you from buying something else. Of course, this is also true in the book industry; buying and reading one book doesn’t preclude you from buying and reading another, a fact for which I as an author am grateful!

Low Barriers to Entry

Sometimes the operative constraint isn’t in what people want (demand), but rather in what can be provided (supply). Even if there were an unlimited number of good ways to design an airplane, for example (which the laws of aerodynamics suggest there aren’t), the enormous cost of producing an airplane combined with the relatively low number of buyers (essentially just airlines, freight companies, and very wealthy individuals) means that there isn’t room in the market for a whole lot of options.

Returning to books, the explosion of available titles occurs not because so many more people want to read books, but rather because it’s so much easier for authors to write and publish them. The same is true for musicians, app developers, video producers, and so forth. Where the means of production were once expensive and scarce, they’re now cheap and accessible.

Enter Long Tail Economics

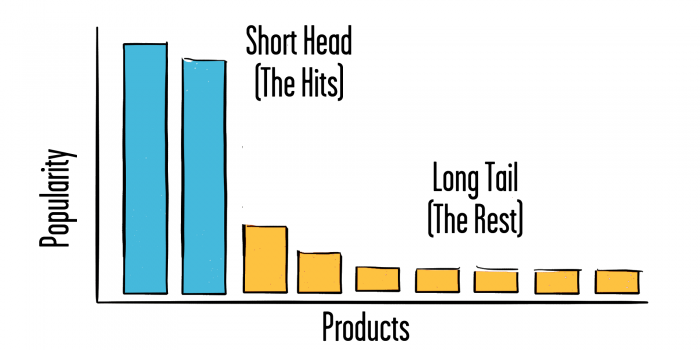

This combination of multiple non-exclusive ways to win and a market with low barriers to entry for new players can create myriad options, with a unique set of economic properties that Chris Anderson described in his 2004 article in WIRED magazine titled “The Long Tail” and his 2006 book by the same name. The “long tail” is a simple concept with powerful implications. Here it is in a nutshell, as articulated by Anderson on his website:

…our culture and economy is increasingly shifting away from a focus on a relatively small number of ‘hits’ (mainstream products and markets) at the head of the demand curve and toward a huge number of niches in the tail. As the costs of production and distribution fall, especially online, there is now less need to lump products and consumers into one-size-fits-all containers. In an era without the constraints of physical shelf space and other bottlenecks of distribution, narrowly targeted goods and services can be as economically attractive as mainstream fare.117

In other words, shelf space in brick-and-mortar stores was a limited commodity; with only so much room, they stocked only stuff that they knew a lot of people would buy (the “hits”). When stores went digital, and the concept of shelf space became meaningless, it let all the “non-hits” into the market for those who wanted them. This is fantastic for all those whose tastes don’t conform to top forty lists in every category!

In aggregate, the yield of long-tail marketplaces can be spectacular; sites like Amazon and iTunes see a substantial portion of their traffic and revenue come from the long tail of titles that most of us have never even heard of. However, this works only because of the immense quantity of those titles; for the artists and producers who live in the long tail, the returns are dismal. Everybody knows about the hits, but hardly anyone has heard of the rest. This is true of YouTube video producers (a third of videos published on YouTube have fewer than ten views), app developers (94 percent of the revenue in the Apple App Store comes from just one percent of all publishers, and 60 percent of apps go un-downloaded), authors on Kindle (the vast majority sell fewer than a hundred books), and so on. Because these platforms rely on volume to succeed, they tend to force pricing models that are great for the hits, but not for everyone else. That’s why success with most opportunities that rely on long-tail economics requires that you move large quantities of inventory on a monthly, weekly, or even daily basis.

Now that we understand how markets fragment, let’s turn our attention back to the topic at hand. We’ve already seen which parts of the education industry will consolidate, so now let’s see which parts will break apart.

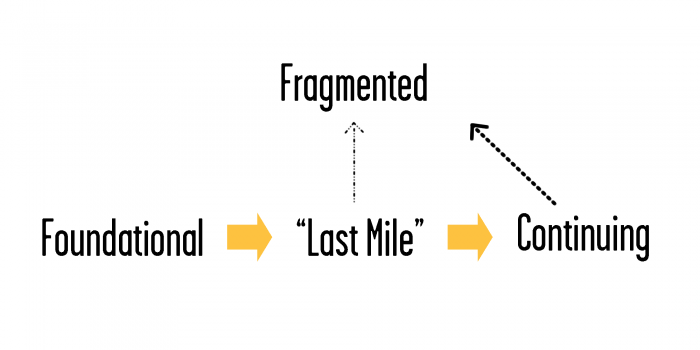

Foundational education will come from a few select providers, and the same is true of major “last mile” trainings and the most popular of continuing education courses. That’s the stuff at the fat head, but what about the long tail? This where the bulk of the education we consume over our lifetimes will come from—short and focused courses delivering just the information, insight, and fortitude that we need, just when we need it. This will include more niche-focused “last mile” education, and the majority of continuing education courses on a plethora of topics. Before we learn where this education will come from, let’s understand why it can’t come from today’s universities and colleges.

Colleges are unlikely to evolve in this direction for all the reasons that make innovation challenging, which we explored in the last chapter. The biggest reason it isn’t going to happen, though, is money: There’s just no way that they can afford it. Here’s why: Of all the challenges and inefficiencies of mainstream higher education today, its ace in the hole has been that education comes in a bundle of at least two years, and usually four. This means that colleges’ vast catalogs of courses, most of which are at advanced or graduate levels usually attended by small numbers of people, historically have been subsidized by the massively attended introductory courses that are mandatory for undergraduates starting their programs. This is doubly true (or rather, five times as true, if you do the math) when you consider that only 21 cents of every tuition dollar actually goes to instruction!118

For higher education, unbundling would drastically reduce revenue per student.

For higher education, unbundling would drastically reduce revenue per student. We’ve seen this pattern before, for example with cable companies making us pay for all sorts of channels that we don’t watch in order to get access to the few that we do. Right now, college works the same way, a fact which won’t be true for much longer. The unbundling of courses from each other and from the college experience as a whole will be devastating to these institutions, as Ryan Craig explains: “For higher education, unbundling would drastically reduce revenue per student. As a result, the cost structure of colleges and universities would need to downshift dramatically.”119 All this comes against the backdrop of an education bubble that is popping slowly, at which point public confidence and the enrollment revenue it has driven into institutions of higher learning will drop precipitously. So try as they might, colleges just won’t be able to play in this arena. The math just doesn’t work.

If not colleges, who will provide the lifelong learning of the future? From the only place that it can come from: the experts and professionals on the cutting edge and front lines of their respective fields. They’re the only ones whose knowledge and skills will be sufficiently up to date to provide what learners will need. While their skill level and opportunity cost will command a premium, the transformation that they will deliver will justify paying it. Some colleges see the writing on the wall, and are scrambling to hire these very experts as “adjunct professors.” This is great proof of concept for the experts, but only a band-aid for the colleges; they’re still hampered from evolving by all the factors that we’ve explored, and experts are already realizing that they have more freedom to innovate and to earn meaningful income without being tied to a university.

Why We Need to Learn from Experts First and Teachers Second

In 1451, an Italian notary named Ser Piero had an affair with a peasant woman named Caterina, and nine months later she bore him a son. Formal schooling was out of the question for an illegitimate child, but Ser Piero wanted his son to find a stable profession. He noticed that the boy had a talent for drawing, and when the boy turned 14, his father arranged for him to apprentice in the workshop of Andrea di Cione, known as Verrocchio, who was considered to be one of the finest painters in Florence. The boy was Leonardo da Vinci.

The apprenticeship model, in which a student studies directly under a practicing master, is common in human history. This would seem to make sense. Who better to learn from than someone actually doing what you’re seeking to learn, on the front lines of the trade? Wouldn’t a practitioner be the obvious choice over an educator or academic any day of the week?

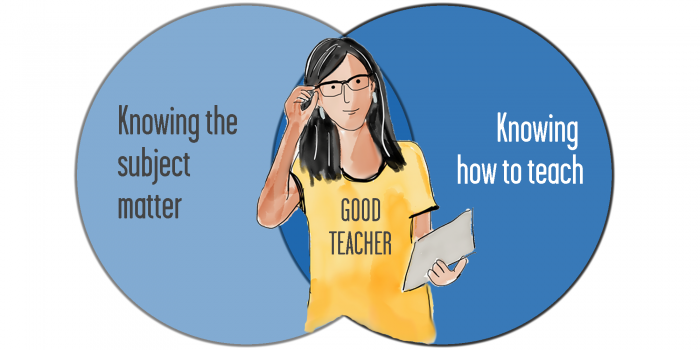

Good teachers are the ones who can, and do, and teach, but that intersection can be a difficult balancing act.

Good teachers are the ones who can, and do, and teach, but that intersection can be a difficult balancing act. Actually, no. There are good reasons why a teacher would be a better choice than a practitioner, the most important being that teaching is hard. It takes patience to move at the students’ pace, skill to reach them where they are, and imagination to understand how things look from their point of view and to find metaphors and examples that help them reach the appropriate conclusions. Teaching is an art and a science, and expecting that being a practitioner of a skill automatically translates to being able to teach it simply isn’t reasonable. Expecting a chess master to be good at teaching chess is a bit like expecting an athlete to be a good coach. Playing chess and being good at basketball are fundamentally different skills from teaching and coaching. Reality is the opposite of the trope: “Those who can, do. Those who can’t, teach.” Good teachers are the ones who can, and do, and teach, but that intersection can be a difficult balancing act.

The question of subject matter knowledge vs. teaching skill isn’t “Which is more important?” (you need both), but rather “Which is harder to develop?” Since most of the history of formal education was characterized by a fairly static curriculum, the answer was the teaching skill. Whether it took a few months to master your times tables in elementary school or a few years to master trigonometry in college, once you got it, you had it. Neither the times tables nor trigonometry are changing anytime soon. The same is true for most topics, whether it’s double-entry bookkeeping, the history of medieval Europe, or the correct form for doing a push-up. The subject matter involved in the job remained static or changed slowly enough that an occasional conference or continuing education course was enough to stay up to date. The rest of the teacher’s time and energy could be devoted to improving their craft of teaching and actually working with students.

But the pace of change has increased, and rapidly, to the point that everything we learn is obsolete within five to ten years. This dramatically changes the game of staying up to date, such that the only practical way to remain as current as needed is to be in the trenches and on the front lines, actually doing the work and learning on the job. This pace of change has necessitated that our priorities shift; while the best choice of educator used to be a great teacher who also knew the subject matter, now the only ones who can do the job are the experts in subject matter who are also great teachers.

But Which Experts?

Imagine for a moment that you’re literally the most powerful man in the world, and your teenage son needs a tutor. Whom do you get to do the job? In 343 BCE, this wasn’t a hypothetical question. King Philip II of Macedonia needed a tutor for his 13-year-old son, so he summoned the leading thinker of his day to be his son’s tutor. The thinker’s name was Aristotle, and the student’s name was Alexander, who grew to become Alexander the Great.

From the king’s vantage point, this makes perfect sense. You want the very best for your child, and you have the resources and authority to make a compelling case to one of the greatest philosophers in history. The role looked good from Aristotle’s vantage point as well; one imagines that tutor to the crown prince would be a pretty good gig. And besides, what else was he going to do?

But modern learners don’t have the resources or authority of King Philip II, and today’s experts have more and better options to choose from than Aristotle did in 343 BCE. The modern equivalent of being tutored by Aristotle might be private instruction on writing with Malcolm Gladwell and James Patterson, filmmaking with Ron Howard and Martin Scorsese, photography with Annie Leibovitz, singing and performance with Christina Aguilera and Usher, cooking with Gordon Ramsay, and chess with Garry Kasparov. They are all leaders in their respective fields and are motivated to share their knowledge by filming a video course for the MasterClass platform, which includes a few dozen videos and even a handful of group Q&A calls with the expert. That’s great, but it’s not a private tutoring relationship, any more than reading The Complete Works of Aristotle can be equated to the learning experience of Alexander the Great.

This isn’t a criticism of the great video courses that these experts have recorded, but rather a recognition that what they offer is akin to reading a book that happens to be in video format. It’s not the sort of transformation that direct access or apprenticeship would create. There’s no other way that this could be, for two big reasons:

- Reason 1: Logistics. There is only one of each of these experts and potentially millions who would want to learn at their feet.

- Reason 2: Opportunity cost. Even if they could directly instruct each person who wanted to learn from them, they’re too busy tending to their day jobs of making movies, composing hit songs, and running restaurants.

You might be able to get around these reasons if you’re the modern equivalent of the king of Macedonia, but otherwise you’ll have to look elsewhere for continuing education. We look one rung down the ladder, to the experts and professionals at the top of their game and the forefront of their field, who haven’t yet written New York Times best-selling books, produced award-winning reality TV shows, or famously beaten every human opponent on the planet only to fall eventually to IBM’s Deep Blue supercomputer. Those experts alone have the combination of cutting-edge knowledge and skills, exposure to work that allows them to maintain their edge, and opportunity cost that means earning extra tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands, or on rare occasions millions of dollars a year is well worth their while.

Of course, we prefer the subset of those experts who also have either the ability or the potential to be great teachers. They are the ones who will supply the highly fragmented demand for some “last mile” education and most of the continuing education courses that we as a society will need to stay current.

Pausing to reflect, we’ve come a long way together. In the first half of this book, we’ve explored why education in its present form is failing us, what it needs to do to carry us into the future, and where we can expect that new education to emerge. The next half of the book will be dedicated to what education will need to look like to get us where we need to go, and how we will go about creating it.

Want to test your understanding of the ideas that we just covered? Or start conversations with interested friends and colleagues? Here are a few questions to guide you:

1. What is fragmentation as it applies to business?

2. What are the conditions that lead to the fragmentation of a market or industry?

3. What does Chris Anderson mean by “the long tail”?

4. Will the education market move towards consolidation or fragmentation?

5. Why can’t continuing education come from today’s universities and colleges?

6. Why is the bulk of the continuing education market likely to become fragmented?

7. Why does it make more sense to learn from a good teacher than from a practitioner?

8. Everything we learn becomes obsolete in 5-10 years. How does this impact continuing education?

9. Is it better to learn from a great teacher or from a subject matter expert?

10. Who will be the best providers of continuing education courses?

Like What You Read, and Want to Go Deeper?

Here are a few good books to take a look at if you’d like to go deeper on some of the ideas presented in this chapter.

- Jeff Cobb’s Leading the Learning Revolution

- My own book, Teach and Grow Rich

And if you’d like to put out your own shingle as an educator entrepreneur, a good place to start is to join one of the free Course Building Bootcamps offered by my company Mirasee; details at LeveragedLearning.co/cbb.