The Changing Landscape of Learning

“btw, forgot to tell u… click ur heels together 3 times and u can go home” –Glinda

“Mom, where are you??? I woke up and nobody’s here!” –Kevin

“Sorry hun, had to run–midnite curfew. Call me tmrw? also I think I lost my shoe.” –Cinderella

“Harry, it was just a dream. I’m fine. Don’t storm the Ministry.” –Sirius Black

“Hey Alfred, Bruce got scared by the opera, can you come pick us up in front?” –Thomas Wayne

“Romeo, I came up with a plan with Friar Laurence. I’m not really dead–lol. Just fyi.” –Juliet

Few things have been as disruptive to story plots as the instant information sharing made possible by text messaging. Just a single text, and Dorothy would never have met the Scarecrow, the Tin Man, or the Cowardly Lion. Kevin’s parents would have known that he was okay, and no murdered parents would have meant no traumatized Bruce Wayne, and therefore no Batman.

Of course, stories might get away with it from time to time, coming up with weird twists explaining why none of the characters have cellular service, or even a phone. But it’s the sort of narrative device that strains credibility and must be used sparingly. We all know that the world today isn’t the same as it was a few decades ago, so we must adapt. The same is true of the way we conceive and consume education.

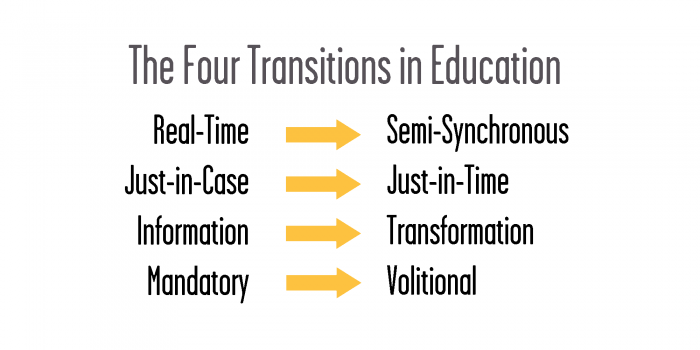

There are four major transitions currently changing the landscape of learning, with the same seismic implications to education as the instant information sharing of text messaging to plots of movies. Each of these transitions underscores shifts in what we want and expect as consumers of education, challenges for institutions who provide it, and opportunities for upstarts to enter the scene.

Have you ever noticed how quickly most restaurants can get any number of dishes ready? Sure, some of this is customer service sleight-of-hand, starting you off with bread or nachos or salad to distract you from waiting for your meal. Even taking that into account, and considering the rush time or occasionally incompetent waiter, it’s rare for a restaurant to need more than ten to twenty minutes to prepare any given dish.

It’s so common that we take it for granted, but the next time you’re in a restaurant, take a moment to consider the items on the menu and ask yourself, assuming you had the recipe and all the ingredients, how long it would take to prepare the same dish at home. With rare exceptions, the answer is much, much longer. So how do restaurants get the job done so quickly?

The answer is in the mise en place, a French culinary term that translates to “everything in its place.” Take a relatively simple dish like an Italian spaghetti primavera, for example. The pasta just needs to be dropped in boiling water for a few minutes. The sauce, however, is more complex. You might start by sautéing onions in oil and garlic, then adding carrots, zucchini, mushrooms, broccoli, and more. A fair amount of preparation is required before you can start cooking: taking the ingredients out of the refrigerator and cupboard, peeling and crushing the garlic, and chopping all the vegetables. That part usually adds up to more time and work than the actual cooking of the meal!

Restaurants know this, so they get things done in advance. The chef doesn’t receive your order for spaghetti primavera and start taking ingredients out of the fridge. The mise en place has already been prepared and placed in little dishes by junior kitchen staffers, ready to go.

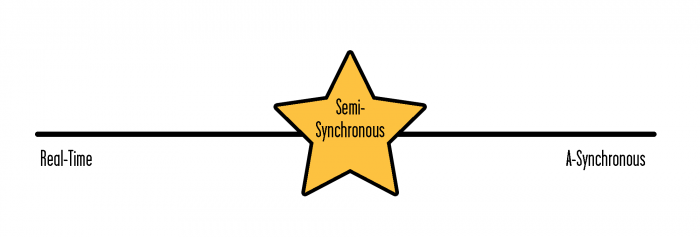

This process is effective because it neatly divides the work of food preparation into two categories: the tasks that need to happen in real-time (the actual cooking that leads to a fresh, hot meal) and the tasks that can be done semi-synchronously, meaning within the bounds of a much wider window (laying out and preparing all the ingredients). Now, it usually isn’t a good idea to do everything a-synchronously (think of how unappetizing microwave dinners often are). But as recent meal-kit providers like HelloFresh and Blue Apron are capitalizing upon, there are compelling time and efficiency savings to be achieved by a-synchronously doing the things that easily can be. The process is the same reason that we generally prefer YouTube and DVRs and Netflix over live television, text messages and email over phone conversations, and Uber over the bus. It works for food, entertainment, communication, and transportation as well as for education.

Semi-synchronous: A New Spin on an Old Idea

The idea of non-synchronous education has been around since at least 1844, when Sir Isaac Pitman founded his Correspondence Colleges in England.74 However, a certificate from Pitman’s Correspondence Colleges back then didn’t carry any more weight than most online courses did as recently as five or ten years ago; it was too far outside the mainstream. Distance learning finally has started to change, thanks to the efforts of MOOCs like Coursera and edX, course platforms such as MasterClass, Udemy and LinkedIn Learning (formerly Lynda.com), and myriad boutique course providers on a plethora of topics, including my own company, Mirasee, in the area of business education. A good parallel for the mainstream acceptance of online courses today is the state of online dating a few years ago; past the point of being odd or taboo, but not yet something that everybody did, and definitely not responsible for nearly one in five marriages.75

Now we can engage the best instructors in the world and make their course materials accessible to as many people as want to participate.

Now we can engage the best instructors in the world and make their course materials accessible to as many people as want to participate. This widespread acceptance is partly a matter of familiarity and partly a matter of convenience, but also largely a reflection of the fact that many features of online courses are just plain better. As Bryan Caplan writes, “Online education has clear pedagogical advantages over traditional education”76—advantages like the ability to cost-effectively run “flipped classrooms.” Students consume the lesson content on their own time, using video that they can pause, rewind, accelerate, and re-watch until they know they’ve got it, then engage with an instructor or their peers. It’s not just any old instructor: Now we can engage the best instructors in the world and make their course materials accessible to as many people as want to participate, regardless of their location, time zone, or schedule.

We’ve been in the 1.0 days of online education, and there’s still an enormous amount of room for growth and improvement. At the top of the list is that line between a-synchronous and semi-synchronous.

You can prepare the mise en place for your spaghetti primavera within a much wider window than the moments before you begin to cook, but that doesn’t mean you can do it anytime. Ingredients can lose their freshness and go bad, so while you can prepare them that day, and maybe earlier that week, it would be a mistake to take a completely a-synchronous approach and chop vegetables for an entire year. Similarly, while much of education can be done semi-synchronously, some things still work best in real-time and face to face. The blending of the two options creates the perfect balance of convenience, affordability, and effectiveness.

Semi-synchronous education also leads to the second major transition in the learning landscape, from just-in-case to just-in-time.

In 1972, Maureen and Tony Wheeler bought a beat-up car and drove from London “as far east as we could go.”77 They wound up in Australia, and along the way they jotted notes about the best things to see, places to eat, and activities to participate in. The couple loved adventure and wanted to discover the world for themselves. Not everyone wants quite that level of adventure, though, and the Wheelers’ notes formed the foundations of an attractive guidebook for people who wanted to dis-cover the world without figuring it all out on their own. That was the beginning of Lonely Planet, the travel guide company.

When it comes to travel, I’m on the opposite end of the spectrum in my appetite for novelty and adventure. The idea of being dropped into an unfamiliar environment and figuring it all out on the fly can bring me close to a panic attack. Most of my travel is for business, and I want to get from the airport to my hotel, with as little adventure along the way as possible.

Thankfully, the combination of credit cards, Google Maps, Book-ing.com, Uber, extensive cellular connectivity, and the ability to search for any information you might need when you need it have made travel almost as smooth an experience as someone of my temperament can hope for. Let’s say I was invited to attend a conference for my first visit to Australia, for example. I wouldn’t need to do much other than pack a bag, get on a plane, and figure the rest out upon arrival. That’s the beauty of our age of just-in-time information and services: Pre-planning is often unnecessary and overrated.

There are a couple of notable exceptions, though. As a Canadian, it would be important for me to know before my trip that I need to arrange a visa to enter the country, that Australia’s location in the Southern Hemisphere means the seasons are flipped (Canada’s winter is Australia’s summer, and vice versa), and that unlike the spiders occasionally encountered in my hometown of Montreal, many spiders in Australia are venomous and should be avoided. Just-in-time is too late for these things; they’re important to know just-in-case. Otherwise I might be turned away at the airport, pack for the wrong weather, or suffer an unpleasant bite.

Anything you learn is going to become obsolete within a decade.

Anything you learn is going to become obsolete within a decade. This is the second major transition in the world of education: from just-in-case to just-in-time. Learning used to be something that you did for a long time at the start of your career, but that just doesn’t work in today’s world. It’s so much easier to access information and training when we need it, and conditions change so quickly that things you learned “just-in-case” are more likely than not to be outdated and irrelevant by the time you actually need them. This isn’t a fringe idea, but rather one espoused even in the academic establishment; Lawrence Summers, former president of Harvard University, went on record saying, “I think, increasingly, anything you learn is going to become obsolete within a decade, and so the most important kind of learning is how to learn.”78 As Jeff Cobb, author of Leading the Learning Revolution explains:

For decades we’ve lived in a ‘knowledge economy,’ one driven by service and information-based businesses. But now knowledge sounds too finite, there are professions where knowledge still works, but we now live in a ‘figure it out on a daily basis’ economy, or a learning economy. The nature of our work is changing from year to year, based off the development of technology.79

And it gets worse – not only is much of what we learn “just-in-case” as likely as not to be outdated by the time we need it, but also, as Rohit Bhargava elaborates in Always Eat Left Handed, the odds that we’ll need much of it are almost as slim as the odds that we’ll remember it if we do:

Since early in grade school, our education is very infrequently connected directly to the world around us. Much of this educa-tion is “just-in-case”—things that we learn either because of tradition or the mistaken belief that that one day we may need to know them or choose a profession that uses them. Calculus, the history of Mesopotamia, how to spot iambic pentameter these are all pieces of knowledge that you may or may not use through the course of your life. Sadly, if a moment arises in the future where you did need to know about any of those topics, chances are you wouldn’t remember enough of what you learned years ago in order for it to be useful anyway.80

The Transition to Lifelong Learning

So if not a mass of education at the start of our careers, then what? As Joseph Aoun, president of Northeastern University in Boston, writes, “It no longer is sufficient for universities to focus solely on isolated years of study for undergraduate and graduate students.”81 The answer is education in smaller increments, spread over our entire lives—what Jeff Cobb calls the “other 50 years.”82 This probably will add up to more education in aggregate; the Stanford 2025 project of reimagining the future of education, for example, predicts that the current four years during the ages from 18 to 22 will be replaced by six years spread over a lifetime.83

This transition to lifelong just-in-time education is underway, as we see from the percentage of increasingly older students partaking in education. Currently 17 percent of the $1.4 trillion of outstanding student loan debt in the United States belongs to people older than 50, and people older than 60 are the fastest-growing age segment of the student loan market.84 As Aoun writes:

Of the 20.5 million students attending U.S. colleges and universities in 2016, 8.2 million were 25 years or older. A full 40 percent of students, therefore, are older than the age generally viewed as ‘traditional’ for college. By 2025, the number of students aged 25 or older is projected to increase to 9.7 million.85

But in a context of lifelong learning, taking a full-time semester for skill development is impractical, to say nothing of one or more years. So courses are shortened and designed to be done on the side, while the rest of life continues to go on. This is the granularization of learning, what Bhargava calls “light-speed learning.” In his words, “The road to mastery on any topic gets faster through the help of bite-sized learning modules that make education more time efficient, engaging, useful and fun.”86 Familiar examples are the courses on platforms like Udemy and Lynda, or those provided by independent professionals. And on the far extreme of granularity is the rising interest in microlearning and learning through apps, like DuoLingo and Smart.ly.

The New Education Ecosystem

So if the consumption of education is trending away from four years at the start of one’s career to something in the range of six years over the course of a lifetime… how will those six years be distributed to have impact and meaning in the students’ lives? Most likely, education will divide into three categories: foundational, “last mile,” and continuing:

Foundational education is the stuff that everybody needs: fundamental knowledge and skills, the ability to generate insight from whatever else you might learn, and the fortitude that is at the core of surviving and thriving in the world. This is what universities today say they do and even try to do, but fail miserably, in terms of both absolute results and return on the time and money invested.

“Last mile” education (hat tip to Ryan Craig, who coined the term87) is the technical training that bridges the gap between a well-rounded foundation and the specific skills that are needed to enter specific career paths. This is currently offered in clunky fashion by law schools and medical schools, as well as by coding boot camps and apprenticeship programs. They may not be efficient or pretty, but these are the bridges from a general education into a specific career.

Continuing education is what we all need in order to stay current in a world where “anything you learn is going to become obsolete within a decade.”88 Currently, this is a mess of executive education, learning on the job, self-study from books and YouTube videos, personal practice, certifications from a smattering of sources, and a variety of online courses from a range of providers, with little in the way of oversight or quality control.

There’s much to be done in all these areas to get to where we need to be. However, we can expect that in the not-too-distant future, a lifelong educational path will begin with one or two years of foundational and “last mile” education, either taken separately or bundled together, with four more years spread over the rest of our lives and careers.

Ashlee “Tree” Branch graduated summa cum laude with a grade point average of 3.941 from High Point University in North Carolina. She had worked hard at her studies, and also worked during her studies as an assistant in the school’s Office of Student Life, then in the Women’s and Gender Studies Department. So her resume was as strong as you can expect a fresh graduate to be when she set out into the workforce in search of a career. She quickly encountered the frustrating Catch-22 facing almost every young job seeker: Employers don’t want to hire you unless you have experience, but of course you can’t get experience until someone takes the chance to hire you. The story ended well for Tree, and for me; she’s a superstar, and when her resume came across my desk in October of 2015, I had the good sense to hire her, and we haven’t looked back since.

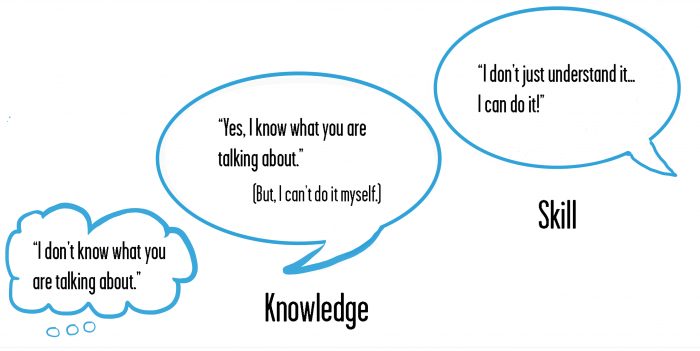

The Catch-22 is challenging and real. Yes, recent graduates have lots of things working against them: the enormous average student debt, the ubiquity of degrees making it hard for them to stand out, and the general misalignment of college curricula with the skills that employers are actually looking for. But employers have an even bigger and more fundamental issue with people fresh out of school: They just don’t know anything. Or rather, they know a whole lot, but they don’t know how to do anything. To quote Stephen R. Covey, “To know and not to do is really not to know.”

The value of information alone has cratered.

The value of information alone has cratered. In fairness, knowledge used to be a lot more valuable than it is today. Back when my World Book Encyclopedia was the best way to find information that I needed, it made perfect sense to pay a premium for the 26-volume set. But those days are long gone. Today we have Google and Wikipedia, with anything we might want to know are just a few keystrokes or a voice command away, the value of information alone has cratered. What really matters is our ability to do something with what we know, and that’s a different kettle of fish.

Learning About vs. Learning To

Pure knowledge is fairly easy to impart. All it takes is a good explanation and possibly a bit of repetition, and you’ve got it. Everything you’ve read in this book so far is a good example of this. I hope that my explanations have been clear, engaging, and cogent enough for you to feel that you’re getting a grasp on what’s wrong with education today, and how it is changing. But that doesn’t mean you’re capable yet of doing something about it. For that you’ll need a lot more than just an explanation!

Developing a competence or skill can start with an explanation and repetition, but it also needs the input and experience of real-world application, a feedback loop that tells whether you’re on the right track or need to correct your course, and gives you the opportunity to make those adjustments and see the results. Although most of the world of education does a decent job of imparting knowledge, it isn’t very good at imparting skill.

For that sort of learning, a classroom doesn’t cut it. Rather, we need experiential education. While representing a minority of the overall education that’s out there today, experiential education is most commonly done through some variation of an apprenticeship or internship, whether it’s cooperative education, part-time or short-term internships, job shadowing, study-abroad programs, service and service learning, or undergraduate research projects.89 When they’re done well, they can be hugely influential and valuable, but most of the time, they aren’t done well at all.

At worst, they’re a way for companies to get cheap labor, schools to benefit from a bit of arbitrage, and students to waste a whole bunch of time filing, fetching coffee, or otherwise doing tasks that have little to do with the skills and expertise that they’re supposed to learn.

Of course, some internships are a lot better; they involve students in interesting and relevant work, and give them the opportunity to gain hands-on, real-life experience. This is extremely valuable for the students, but still a cop-out for the teachers, who basically are conceding that they can’t design a curriculum more effective than just dropping the student into a real-life situation and hoping for the best. That is fine, but it obviates the need for the instructor!

Only the best of these programs alternate real-world experience with relevant classroom learning and deconstruction of that experience (sometimes called a “blended learning” model), which is what it really takes for this model to work well. And we need it to work, because if students don’t experience a real transformation, there’s no point to the education. Which is especially tough, because transformation for one person might not be transformation for another.

The Jagged Path to Transformation

In 2006, Sir Ken Robinson stepped onto the red dot that marks center stage at the TED conference, to deliver his now famous talk titled Do schools kill creativity? He recounted the story of Gillian Lynne. As a child in the 1930s, Gillian couldn’t stop fidgeting. The school complained to Gillian’s mother, who took her to see a specialist. After a lengthy conversation with Gillian’s mother, the specialist left Gillian alone in a room, and turned on the radio. He and Gillian’s mother watched as she started dancing to the music, leading to his diagnosis: “She isn’t sick,” he told Mrs. Lynne, “she’s a dancer.”

That diagnosis turned out to be right on the money. Gillian Lynne grew up to become one of the most successful choreographers in history, with major broadway credits to her name like Cats and Phantom of the Opera. The learning specialist in this story should be commended, for two reasons. The first is that he didn’t diagnose her as sick and put her on whatever the 1930s equivalent of Ritalin would have been. The second, though, is that he had the insight to see a special talent that was unique to Gillian.

In the previous chapter, we explored how being relevant in the modern age requires that we lean into the things that we’re good at, and computers aren’t. But we aren’t all good at the same things. This is the research focus of Harvard professor Todd Rose. Whereas most learning experiences are designed around the idea that people are more or less the same, Rose argues that no one is truly average—we’re all strong in some areas, and weak in others.90 One person might have exceptional reading and writing abilities, yet be frustrated by the spatial reasoning required in geometry. Another student might love science and dream of running her own experiments, while also being a slow reader who gets flummoxed by the explanations in textbooks. Yet another person might have trouble sitting still in class, but have the potential to be one of the world’s greatest choreographers.

For learning to be truly transformative, then, it has to be customized around the unique strengths and opportunities available to the learner in question. Which has the added benefit of being more engaging to the student, at a time when just holding a student’s attention is getting harder and harder.

In 2011, Sebastian Thrun’s Introduction to Artificial Intelligence course at Stanford University was made freely available online to anyone who wanted to participate. The 160,000 registrants were enough of an impetus for Thrun to leave Stanford and found a massive open online course (MOOC) company called Udacity. His work was so impressive and inspiring that the following year he won the Smithsonian American Ingenuity Award in Education.91

By 2013 the bloom was coming off the rose. Despite having signed up 1.6 million students for his online classes, he decided to pivot away from MOOCs. Why? Quite simply, the concept didn’t seem to work; only seven percent of students in the online courses actually made it to the end.92 Udacity wasn’t unique in this regard; a fair amount of investigation has shown that the completion rate of MOOCs across the board tends to max out at 15 percent.93 To put that in perspective, even the abysmal graduation rates of for-profit colleges such as the University of Phoenix see an online course completion rate of 17 percent.94 The model of a massively open online course seemed flawed, so Thrun turned his attention to new opportunities like nanodegrees.

Why are MOOC completion rates so incredibly low? Do students not want to learn? Are people fundamentally incapable of following through on ventures that they set out to do? Maybe the reason is a lot simpler: perhaps MOOCs just offer too much freedom and choice.

Consider this: For almost the entire history of education, it wasn’t optional. Take K-12 education, for example. Laws vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, but by and large parents are considered criminally negligent if their children don’t go to school. So as kids, we go because we must. The same is true of continuing education provided by employers; if your boss tells you to go, and you want to keep your job, you go. No questions asked.

Then there’s the education that isn’t quite mandatory, but almost. For example, attending college isn’t a legal requirement, but it is so ingrained into the culture that many people feel as if it needs to be done, no matter the cost. There’s also the matter of sunk cost, and how much of an investment we can afford to abandon. Even if undergraduate or graduate education isn’t technically mandatory, once we’ve signed the papers and taken on the debt, we’re committed.

But as we saw in the transition from just-in-case to just-in-time, education is changing from a single decision to participate in a four-year program at the start of a career, to a combined total of six years worth of education in small increments, comprised of and dozens of individual decisions across our lifetimes.95 Rather than the commitment that comes from tens of thousands of dollars of debt plus tens of thousands of dollars of opportunity cost, each decision comes at a cost of hundreds or thousands of dollars plus a few weeks or months of part-time commitment. It’s not that we set out to lose time or money, but these are amounts that we can afford to walk away from.

We used to have structure imposed on us as well; once you start a class, you know that you must be in Room 407 every Tuesday at 3 p.m. But as courses go online and semi-synchronous, as with MOOCs, you can start anytime, consume the lessons whenever you want, and take as long as you like to go through the entire the course. The choice and freedom to dictate everything about our educational journey is great for creating accessibility, but challenging in imposing the burden of self-management on students who aren’t ready for it.

No, Attention Spans Aren’t Shrinking

Perhaps you’ve heard the Internet statistic that our attention spans are shorter than that of a goldfish. This is total nonsense, and anyone who believes we have dwindling attention spans in an age of binge-watching hours of shows on Netflix needs to re-evaluate personal assumptions. The statistic comes from the sensationalization and misreading of a 2015 study conducted by Microsoft, which showed that it took about eight and a half seconds for the subjects’ attention to wander from whatever was put in front of them.96 Our so-called “shrinking attention spans” aren’t a measure of distractibility, but rather of discernment. What it really tells us is that it took eight and a half seconds for the participants’ minds to begin wondering if there might be something more interesting or worthy of their attention.

Our so-called “shrinking attention spans” aren’t a measure of distractibility, but rather of discernment.

Our so-called “shrinking attention spans” aren’t a measure of distractibility, but rather of discernment. That’s a challenging reality for many educational experiences, which have had the luxury of a captive audience that made it unreasonably easy to compete for their students’ attention because they didn’t have to. But now they do because the competition to a lecture, training, or video isn’t the instructor down the hall. Every time we log into a class takes willpower. And how our experience with each lesson—positive or negative—measures up against the alternatives (catching up on Netflix, viewing TED Talks videos, or playing games) affects how much willpower we’ll need to log in the next time.

There are two approaches that course creators can take to overcome this challenge. The first is to take away some choice, by bringing back start dates, end dates, and deadlines that must be met to remain a student in good standing. In other words, it’s dialing back from a-synchronous to semi-synchronous. This is a key factor why Seth Godin’s altMBA boasts completion rates of 96 percent.97

The second approach is to develop courses engaging enough for students to choose them over everything else vying for their attention. This is difficult and expensive, requiring a combination of excellent and/ or celebrity instructors, planning and storyboarding, interaction and community. Good early examples of work being done in this area can be found with MasterClass and with Jumpcut, a Los Angeles-based startup.

The way that education is being delivered is shifting from real-time to semi-synchronous, from just-in-case to just-in-time, from information to transformation, and from mandatory to volitional. That’s a lot of changes, and each is as disruptive to the educational status quo as a phone with text messaging capabilities would have been to the plots of The Wizard of Oz, Home Alone, or Batman. None of these are hypothetical cases or futuristic guesses. They’re all here now, changing the process of how we consume and deliver education.

In the last chapter we explored the changes to what we teach, and now we’ve also covered the changes to how we teach. There’s one very important question to answer, which is: who will provide the education of the future? The next two chapters will answer that question, through an exploration of the economics of education.

Want to test your understanding of the ideas that we just covered? Or start conversations with interested friends and colleagues? Here are a few questions to guide you:

1. What are the four transitions that are reshaping the landscape of learning?

2. What are the pedagogical advantages of online education over traditional education?

3. How is semi-synchronous different from real-time or a-synchronous education?

4. What is the difference between just-in-case and just-in-time education?

5. People used to prepare for careers by undertaking four years of focused studies during the ages of 18-22. According to the Stanford 2025 project on the future of education, what will this be replaced with?

6. Why is information (“learning about”) no longer enough as an outcome of education?

7. What is meant by “experiential” education?

8. The typical completion rates of online courses are dismal, usually ranging from 7-15 percent. Why is that?

9. “Humans have shorter attention spans than a goldfish.” True or False? Why?

10. What are the two approaches online course creators can take to improve completion rates?

Like What You Read, and Want to Go Deeper?

Here are a few good books to take a look at if you’d like to go deeper on some of the ideas presented in this chapter.

- Jeff Cobb’s Leading the Learning Revolution

- James Stellar’s Education That Works