Education for the Age of Acceleration

When Aldous Huxley published Brave New World in 1932, it was hailed as a masterpiece. His picture of a dystopian society more than six centuries into the future was mind-blowing, complete with humans manufactured in artificial wombs, babies indoctrinated into castes, and all pain eliminated by a drug called Soma.

Amid those frightening futuristic predictions were some that, from our vantage point, are mostly amusing and quaint. Take the elevator scene in chapter 4, for example. In Huxley’s day, elevators were mechanical contraptions operated by liftmen, whose job was to maneuver the elevator to your destination by pulling the appropriate levers. Huxley realized that the idea of this being done by a human being so far into the future was laughable, so he imagined a suitably dystopian solution: a genetically engineered sub-human creature of the lowest caste.

You read that right. Huxley could imagine elaborate genetic engineering, but the idea of simply pushing a button and getting where you want to go eluded him. It seems obvious to us now, but Huxley was writing well before the electronic revolution, so there was no frame of reference for anything operated by a computer.

This is a common theme in science fiction; it may include a big idea for how things might be different, but the rest is imagined to remain strikingly the same.

Star Trek, for all that it got right with its vision of a bold egalitarian future, still had women wearing miniskirts in space.

The Jetsons, for example, is essentially a depiction of family life in the 60s, with the addition of jetpacks, spaceships, and food pellets. Star Trek, for all that it got right with its vision of a bold egalitarian future, still had women wearing miniskirts in space. And while it was a big step forward to have an African-American woman on the bridge, let’s not forget that her job was to answer the space telephone.

I heard just this sort of prediction of the future at the 2018 conference of the Association for Talent Development. With 12,000 learning professionals attending from all around the world, and keynotes from the likes of President Barack Obama and management guru Marcus Buckingham, it’s among the world’s biggest conferences on the business of learning. On the morning of the first day, I joined a conference session about the future of education.

The experience was underwhelming, to say the least. The session began with dimmed lights and a video. For five minutes, we watched bombastic facts about the present and projections about the future flash on the screen:

“China will soon become the NUMBER ONE English speaking country in the world, and India has more honors kids than America has kids.”

“The top 10 in-demand jobs in 2010 did not exist in 2004. We are currently preparing students for jobs that don’t yet exist using technologies that haven’t been invented in order to solve problems we don’t even know are problems yet.”

“If Facebook were a country it would be the third largest in the world. (behind China & India).”

“We are living in exponential times. There are 31 billion searches on Google every month. Today, the number of text messages sent and received everyday exceeds the total population of the planet.”

“The amount of new technical information is doubling every two years. For students starting a four-year technical degree this means that half of what they learn in their first year of study will be outdated by their third year of study.”

All these pronouncements were made against the backdrop of a chanting refrain, “right here, right now!” It was a slightly updated version of Karl Fisch and Scott McLeod’s original Shift Happens video,43 which I first watched in 2008 — an ironic start to a presentation about the future! And it was all downhill from there, with discussions about the need for educators to use more technology, make the student’s smartphone part of the learning experience, and leverage resources like TED Talks as part of lectures. Those are all good ideas, but in terms of thinking about and preparing for the future, it’s a Jetsons level of prediction and imagination.

Lectures are among the least effective pedagogical devices known to man.

Lectures are among the least effective pedagogical devices known to man. Worst of all, it was a lecture. Sure, there were some videos and a few “high five and discuss with the person sitting next to you” moments, but it was still a lecture. And lectures are among the least effective pedagogical devices known to man. That’s one of the biggest ironies: that most every class I’ve taken on “cutting-edge adult learning” has been taught using all the modalities (lectures, trivial homework, facile tests) that aren’t cutting-edge adult learning.

Finally, I gave up and walked out of the session. Never mind the future of education, this wasn’t even an accurate picture of the present of education!

The conference presentation can be forgiven for being a little out of date and out of touch. They’re good people who care deeply about their work, but the sad truth is that they’re probably just a little too close to the problem.

There is one important insight about predicting the future in the video’s refrain of “right here, right now.” Imagining the distant future is very hard. As my colleague Rohit Bhargava, author of the Non-Obvious book series about predicting trends and winning the future explains, it’s both easier and infinitely more useful to extrapolate from what’s happening now than it is to make up what might happen later.

The only way education can be sustainable and legitimate is to deliver an outcome that is meaningful in the present and future world.

The only way education can be sustainable and legitimate is to deliver an outcome that is meaningful in the present and future world. As Kevin Carey argues in The End of College, the only way education can be sustainable and legitimate is to deliver an outcome that is meaningful in the present and future world.44 But what will it take to do that? Joseph E. Aoun, president of Northeastern University, wisely wrote that “the existing model of higher education has yet to adapt to the seismic shifts rattling the foundations of the global economy.”45 So what are those changes?

It would be a cop-out to satisfy ourselves with an acknowledgement that we’re all more digitally connected than we used to be, and therefore education needs to use more technology. That’s Jetsons-level prediction, again, obvious (no kidding, we’re using more technology), but neither insightful nor helpful. (The proliferation of technology in learning is much less about doing things on our phones and much more about the capability for a-synchronous and semi-synchronous just-in-time learning.)

We need to understand the seismic shifts that call for us to change not only how we teach, but also what we teach, in order for our students to be ready and relevant. What’s happening right here, right now, that will make the world substantially different later?

One of the hotter topics in the technology press in recent years is that of autonomous vehicles, also known as self-driving or driverless cars. The concept has been in various forms of research and development for decades, but in the past few years there’s been a substantial acceleration (no pun intended), with hundreds of millions of miles of autonomous driving under the belts of leaders in the field,46 like Google, Tesla, Uber, and Mobileye. Tech companies are not alone in this trend; automakers ranging from Audi to Volvo have also invested heavily in building a driverless experience.47

Whether driverless vehicles are a good thing or not is a matter of debate, with strong arguments on both sides. On the plus side, there’s safety (more than 90 percent of traffic accidents are attributable to human error),48 productivity (at an average of 26 minutes each way to work, five days a week, fifty weeks a year, that’s a collective 3.4 million American person-years that could be redeployed),49 and affordability (millions of people work in transportation, and even assuming an entry-level salary, they represent tens of billions of dollars of cost, which can be saved and passed on to consumers).50 That brings us to the argument for why it’s a bad thing. Transportation is one of the largest industries in the world, and automation is expected to lead to massive job loss.

What most pundits agree on is that it isn’t a matter of if, but rather when. The more bullish might argue for commercial driverless cars on the road in just a few years, and the more bearish might think we’re a decade or more away. My personal belief is that it probably will be closer to the latter, based on the maturity of technology, constraints of insurance and legislation, and a timeline for public willingness to get on board. Even in the most pessimistic perspectives, there’s no question that when my children (born in 2015 and 2016) reach what we now call “driving age”, they’ll think of driving their own vehicles the same way we think of when our parents or grandparents would drive without seat belts or ride bicycles without helmets: “What do you mean, you drove your own car… that’s so dangerous!”

Bellwether for the Age of Acceleration

I’m excited to ride in a driverless vehicle, but what’s most interesting for our purposes is the confluence of technologies that will make such a ride possible, and what they tell us about what our world is fast becoming. These technologies and changes have much broader implications than the automotive and transportation industries; they’re the bellwethers of what Thomas Friedman calls the Age of Acceleration, which is the environment that modern education must prepare us for.

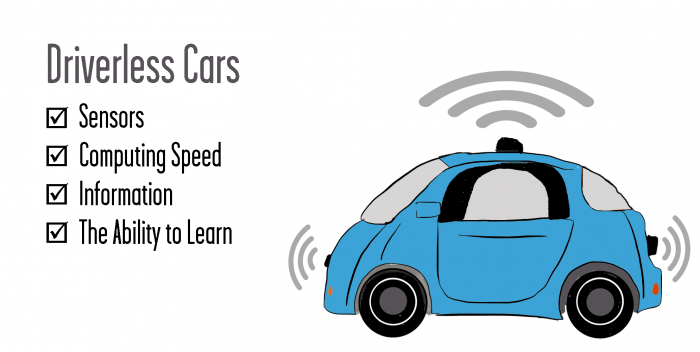

So let’s consider these technologies, and their implications. Building a truly autonomous car takes a lot, including:

- Sensors that can see and hear what is going on around the vehicle. Check. We already have sensors that can replicate sight, hearing, touch, and taste, and smell is on the way. Not only does the technology exist, but also it’s small, cheap, and hardy enough that we can put sensors in almost anything, ranging from industrial equipment to the “connected cow,” a network of sensors attached to every member of the herd that tracking all manner of data for purposes of improving herd management and milk production.51

- Computers fast enough to process all that data. Check. Fifty years ago, Gordon Moore, the co-founder of Intel, famously originated Moore’s Law, predicting that every couple of years processor speeds will double, and their prices will drop in half. This has held true for the past fifty years, despite frequent predictions of its impending demise, leading jaw-dropping (and jaw-droppingly affordable) processing speed and power. Case in point: In 1996 the U.S. government commissioned the ASCI Red, a supercomputer that was the size of a tennis court, cost $55 million, and could process more than a trillion calculations per second for complex simulations. It was the most powerful computer in the world until the year 2000,52 but by 2008 ATI was selling a Radeon HD 3870 X2 graphics card with the same processing power for only $450.53

- Knowledge of the geography and traffic around you, and software smart enough to make driving decisions. Check. This has been around for a while and is used by millions, through services like Google Maps and Waze. Movements like open source and tools like application programming interfaces allow for software complexity to be abstracted away, which means that software developers don’t have to understand the full complexity of existing software to build on it.

- The ability to make smart decisions, learn, and improve, both for individual vehicles and an entire fleet. Check. Complex rules-based software engines allow driverless vehicles to make complex driving decisions, similar to the technology that allowed IBM’s Deep Blue computer to beat Garry Kasparov in 1996. Machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms allow driverless vehicles to learn from their experience and get better—like the technology that Deep Mind’s AlphaGo used to beat Lee Sedol in 2016,54 and Carnegie Mellon’s Libratus beat four top poker players in 2017.55 But unlike any of those systems, driverless cars are all networked to one another, which means each of them learns the lessons from the experience of the entire fleet.

As wondrous and incredible (or scary) as all these advances may sound, none of them are science fiction.

As wondrous and incredible (or scary) as all these advances may sound, none of them are science fiction. As wondrous and incredible (or scary) as all these advances may sound, none of them are science fiction. They all exist today, albeit more so in some places than others. They are already in the process of proliferating into every area of life. So what happens in a world where everything is aware of its state and surroundings, is connected to everything else, and is smart enough to make decisions? The implications for our economies and job markets are profound, which in turn changes the work that education needs to do in order to prepare us for it.

Consider the faint “drip, drip, drip” that you might hear from a leaky pipe in your kitchen. If you catch it early, the fix is cheap and easy. If left to fester, the result can be messy and costly to remedy.

The same thing happens underground with municipal piping. A leak leads to the same “drip, drip, drip,” but nobody can hear it. So the problem festers until it gets big and messy, at which point entire stretches of highway have to be dug up, at a cost in the range of $1 million per mile.56 That is, unless a sensor attached to the pipe can tell you if there’s a problem before it gets that far and exactly where to dig. And sensors on pipes are just one illustration of the many ways in which the artificial intelligence and automation technologies we just explored will disrupt the job market. As Martin Ford explained in Rise of the Robots, “…we are, in all likelihood, at the leading edge of an explosive wave of innovation that will ultimately produce robots geared toward nearly every conceivable commercial industrial, and consumer task.”57

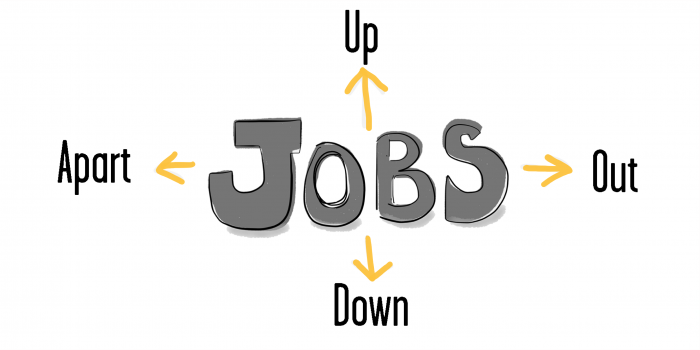

An ounce of prevention really can save a pound of cure, and that’s great if you’re the one paying to relieve the pain, but not so great if your livelihood comes from providing the cure. Just as a few hundred dollars’ worth of sensors can save a few million dollars’ worth of repairs down the road, the various technologies we’re discussing create the potential for massive disruption to the employment market. Thomas Friedman describes four directions in which jobs will be pulled:

- Up: You’ll need increasing amounts of knowledge and skill to perform the same job. For example, automation of milking cow herds means that a herd manager will need computer and data analysis skills.

- Apart: The skilled parts of a job will require even more skill and knowledge, while the unskilled parts will require even less. Continuing with the automated milking example, the milker will need more skill, but the manure shoveler will need less. The job probably will be performed by two people or even more likely, by one person and one machine.

- Out: Outsourcing and automation will compete successfully for more jobs, and for bigger portions of jobs that still require humans. Given that computers and machines are stronger and faster than we are, and they don’t get tired or make sloppy mistakes, it’s a competition that humans aren’t likely to win.

- Down: As the world evolves, jobs, skills, and knowledge become obsolete at ever faster rates. As articulated in the Shift Happens video, “for students starting a four-year technical degree, this means that half of what they learn in their first year of study will be outdated by their third year of study.”58

Headed for Disruption

In short, we’re headed for a job market disruption the likes of which we’ve never seen before. A frequently quoted 2013 Oxford University white paper forecasts that 47 percent of jobs could be eliminated by smart technology during the next two decades, and a 2017 McKinsey & Company report predicts that 49 percent of the time we spend working (which translates to more than $2 trillion in annual wages in the United States alone) could be eliminated by current technology.59

We’re headed for a job market disruption the likes of which we’ve never seen before.

In consulting firm PWC’s 2018 Workforce of the Future report, 37 percent of respondents were concerned about automation putting jobs at risk.60 Some predictions are even more grim, as Joseph E. Aoun shares in his book Robot-Proof:

In late 2016, the White House’s National Science and Technology Council’s Committee on Technology released a report titled Preparing for the Future of Artificial Intelligence. In its heavily footnoted fifty-eight pages, the report offers policy recommendations for dealing with machines’ imminent capacity to “reach and exceed human performance on more and more tasks.” As the report ominously notes, “In a dystopian vision of this process, these super-intelligent machines would exceed the ability of humanity to understand or control. If computers could exert control over many critical systems, the result could be havoc, with humans no longer in control of their destiny at best and extinct at worst.”61

So is this the end of the world as we know it? Should we grab our rifles and fill our bunkers with bottled water and canned goods? No, not quite.

What’s coming qualifies as a serious disruption to the economy and labor market, but let’s be real for a moment: These things have happened before. The classic example is when Edwin Budding invented the lawn mower in 1830. It doesn’t sound like a big deal until you consider that it sparked an explosion of sports innovation, which led to the creation of the professional and codified sports industries. That’s right: Professional football, baseball, soccer, and more owe their existence to what is now called the Budding Effect,62 that is, the unexpected opportunities created when things change. In the case of professional sports, the simple fact of having even, level mowed fields opened up a cornucopia of possibilities that had yet to be imagined.

We can expect the same thing to happen in the convergence of “STEMpathy” work (where the technical skills of science, technology, engineering, and math meet the humanistic skills of empathy and connection), but it’s hard to say exactly where. We just aren’t good at seeing these changes coming, for the same reasons that Aldous Huxley couldn’t predict an electronic elevator, and that Star Trek imagined women would wear miniskirts in space. We’re not good at imagining the implications of the implications of the implications of things that change. But historically speaking, this has happened over, and over, and over again.

So if we know that the Budding Effect will bring lots of jobs and opportunity into our world… but we don’t know what they are, and can’t see them coming. But we aren’t flying totally blind. We do have a sense of what category of challenges they’re likely to fall into.

Simple Vs. Complicated Vs. Complex

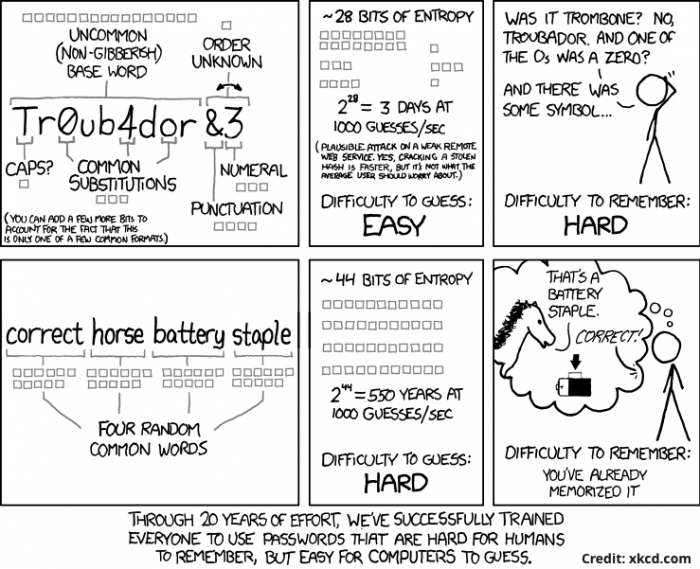

Computers are getting smarter every day, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t areas in which we’re much better than they are and will remain so for the foreseeable future. However, our strength probably isn’t in the areas that many of us might imagine. Our intuition is actually bad at assessing what is easy and what is difficult. A good illustration is this comic from KXCD, which can be found online at https://xkcd.com/936/:

The things that we think of as hard are things that our brains aren’t really wired to do, but we figured out ways to do anyway—things like math and physics and playing chess—but these things are trivially easy for a computer. It would be virtually impossible, for example, for a human to calculate π (pi) to a million decimal points, or memorize the geography of an entire city and calculate the fastest route from point A to point B, but a computer can do it in seconds.

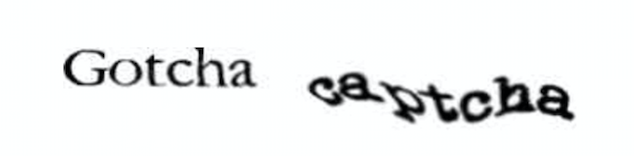

On the other hand, the things that we think of as easy are things that our brains evolved for millions of years to be good at. This means that we have incredibly intricate and elaborate neural circuitry for doing them, so efficiently that the task seems trivial until we put it in front of a computer. For example, take the challenge of reading this word or telling which animal in the image below is a dog. Piece of cake for us, yet impossibly hard for a computer.

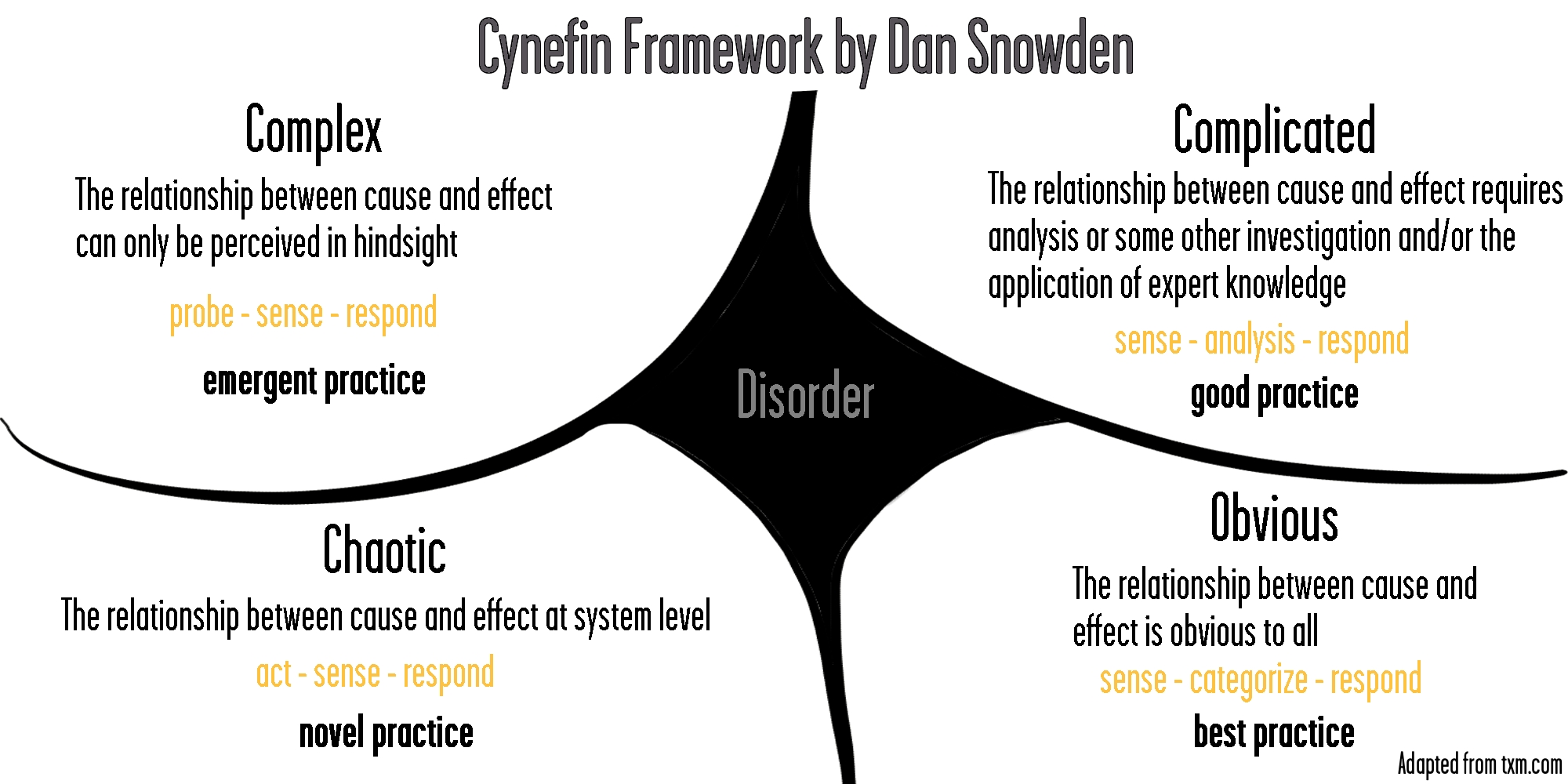

What sorts of tasks are unlikely to be ceded to computers in the coming decades? In 1999, Dave Snowden, a Welsh management consultant, developed what has been called a “sense-making device” that draws on research in systems theory, complexity theory, network theory, and learning theories called the Cynefin framework. It divides the world into four decision-making contexts or “domains:”

- Obvious, where there is a clear relationship between cause and effect, meaning that best practices can be easily documented, and solutions can be applied algorithmically.

- Complicated, where analysis and investigation based on training and expertise are required to identify the relationship between cause and effect.

- Complex, where the relationship between cause and effect are clear only in retrospect, and problems are solved by trialing new solutions.

- Chaotic, where there is no clear relationship between cause and effect, but we have to act anyway.63

Since the twentieth century, the working world has rotated through these domains. The first to fall to technology was the obvious tasks, and the rise in credentialism (i.e. degrees) originated with the need to train people for complicated work. Now intelligent machines and algorithms are starting to play in the realms of the complicated and sometimes even the complex, which is where massive job loss is going to come. In other words, it isn’t jobs as a whole that are going away, so much as what Dutch historian Rutger Bregman, author of Utopia for Realists, calls “bullshit jobs” that dumb us down and drain us of our humanity.64

There will still be lots for us to do in the complex and chaotic domains that computers can’t handle. But we need a very different set of skills in order to do them, and sadly today’s education isn’t doing a great job of empowering us with those skills. As British-American entrepreneur Andrew Keen writes in How to Fix the Future:

The truth, however, in America at least, is that the children aren’t being taught well. A May 2017 Pew Research Center report, The Future of Jobs and Jobs Training, asked 1,408 senior American executives, college professors, and AI experts a series of questions about the challenges of educating people for an automated world. The Pew report found that 30 percent of them expressed no confidence that schools, universities, and job training will evolve sufficiently quickly to match the demand for workers over the next decade. “Bosses believe your work skills will soon be useless,” the Washington Post bluntly concluded about the report.65

How should we approach this challenge? How do we go about preparing students for jobs that don’t exist yet, using technologies that haven’t been invented, in order to solve problems we don’t even know are problems yet?

In 1971, political philosopher John Rawls proposed a thought experiment for designing a perfectly just society: Imagine that you know nothing about the particular talents, abilities, tastes, social class, and positions that you will be born with. Now design a political system. This exercise, called the “veil of ignorance,” works because when you don’t know which place in society you might end up, you’ll take care to design a system that is fair, just, and compassionate to everyone.

It’s a clever approach, so we’ll take a page from Rawls’ book to design the perfect education for the future. Imagine that you’re about to undertake the most important project of your life and career. It is high-profile and sensitive, and it holds great potential for both upside and downside… and that’s all you know about it. Nothing relating to the specific field of operation, scope of work, or tasks involved. Now select the people you would want to work on it as part of your team. Because you don’t know anything about the specifics of the project, specialized skills aren’t useful as selection criteria. It doesn’t make sense to recruit a mechanical engineer when the project might have nothing to do with mechanical engineering. So other than basic foundational knowledge such as literacy and numeracy, you’ll probably select for the softer skills, like creativity and resourcefulness, work ethic and reliability, learning and adaptability, and the ability to lead and play well with others. Or, put more eloquently by Andrew Keen:

The challenge (and opportunity) for educators, then, is to teach everything that can’t be replicated by a robot or an algorithm.

For Carr, with his vision of the profound limitations of computers, that includes the nurturing of intuition, ambiguity, and self-awareness. For Daniel Straub, the former Montessori educator, it is the teaching of consciousness and the idea of a calling. And for Union Square Ventures’ Albert Wenger, who is homeschooling his three teenagers, it’s teaching the self-mastery enabled by psychological freedom. This is the humanist ideal of education [Thomas] More laid out five hundred years ago in Utopia. It’s the teaching of the unquantifiable: how to talk to one’s peers, how to realize self-discipline, how to enjoy leisure, how to think independently, how to be a good citizen.66

This is precisely the sort of thought exercise that we need in order to “skate to where the puck is going.”

This is precisely the sort of thought exercise that we need in order to “skate to where the puck is going.” You might think, “But how could I possibly build a team for a project without knowing anything about what it will entail?” Yet that’s exactly what educators must do. When looking at a complex and chaotic future in which our students will solve problems that we don’t yet know are problems with technologies that haven’t been invented, this is precisely the sort of thought exercise that we need in order to “skate to where the puck is going.”

Not So Hypothetical After All

And it turns out that this hypothetical exercise isn’t so hypothetical after all, because these are precisely the skills that lead to career success. Research conducted by Harvard University, the Carnegie Foundation, and Stanford Research Center has concluded that 85 percent of job success comes from having well-developed soft skills and people skills.67 And eighteen months after being hired, 54 percent were discharged, and in 89 percent of cases it was because of attitude rather than skill.68 As Ryan Craig reports:

According to Peter Cappelli, director of the University of Pennsylvania Wharton School’s Center for Human Resources and former co-director of the US Department of Education’s National Center on the Educational Quality of the Workforce: [The employers’] list is topped not by a cluster of missing technical or academic abilities but by a lack of work attitude and self-management skills such as punctuality, time management, motivation and a strong work ethic. Indeed, the absence of these traits, which used to be called ‘character issues,’ repeatedly shows up as a primary concern in numerous studies.69

That is probably why employers are so desperately searching for candidates with these skills. In 2009 the Business Roundtable con-ducted a survey asking employers to rank the most important work skills missing among recent high school graduates. The biggest complaints were about attitudes and self-management skills. We have to go down to the eighth item on the list to find something that might be taught explicitly in schools (oral communication) and fourteenth on the list to find a traditional academic subject (reading skills).70 In a 2013 study, 93 percent of employers agreed that candidates who demonstrate a capacity to think critically, communicate clearly, and solve complex problems are more important than their undergraduate major.71 And in an annual survey by Express Employment conducted in April of 2017, employers were asked to rank twenty factors they consider when making hiring decisions. Consistent with the results of the past several years, work ethic was at the top of the list.72 As Joseph Aoun further explained:

According to a 2016 survey of employers, the skill cited as most desirable in recent college graduates is the very human quality of “leadership.” More than 80 percent of respondents said they looked for evidence of leadership on candidates’ résumés, followed by “ability to work in a team” at nearly 79 percent…Written communication and problem solving—skills more commonly attributed to a liberal arts education than a purely technical one—clocked in next at 70 percent. Curiously, technical skills ranked in the middle of the survey, below strong work ethic or initiative.73

The verdict is clear: To succeed in the Age of Acceleration we need soft skills, and the intangible but critical things like work ethic and initiative. Employers know this, but there’s just one little problem: The majority of the items on this list are generally considered to be traits that people either have or don’t. This fundamental reorientation of what we want education to achieve has led to big changes in how that education is conceived and delivered. We’ll explore those changes in the next chapter.

Want to test your understanding of the ideas that we just covered? Or start conversations with interested friends and colleagues? Here are a few questions to guide you:

1. Why is it so very hard to imagine what the distant future might look like?

2. Why is it important for educators to understand the implications of sensors, artificial intelligence, and automation on the global economy?

3. What are the technologies that are making driverless cars an imminent possibility?

4. Thomas Friedman describes four directions in which jobs are being pulled by various technologies. What are these directions?

5. A 2013 Oxford University whitepaper forecasts that 47 percent of jobs could be eliminated by technology in the next two decades. What kinds of jobs are likely to be technology-proof?

6. What is the Budding Effect?

7. What sort of things are hard for us, but trivially easy for a computer?

8. What sort of things are trivial for humans to do, but very hard for computers?

9. Describe the four domains of decision-making according to the Cynefin framework.

10. Of the four domains under Cynefin framework, which ones are going to be difficult for computers to handle? Why?

11. What is the Veil of Ignorance, and what does it have to do with the future of education?

12. Why are soft skills more likely than technical skills to be valuable in the workplace of the future?

13. Based on surveys, what skills and qualities do employers find most important?

Like What You Read, and Want to Go Deeper?

Here are a few good books to take a look at if you’d like to go deeper on some of the ideas presented in this chapter.

- Thomas Friedman’s Thank You For Being Late

- Joseph E. Aoun’s Robot-Proof

- Martin Ford’s Rise of the Robots

- Klaus Schwab’s The Fourth Industrial Revolution