Where Do We All Go from Here?

A couple years ago, I had a few hours to kill on a layover in Chicago. I wandered the terminal, looking for something interesting. I mostly found fashion brand stores and restaurants, but then I found a store filled with a variety of tech gadgets, the unifying theme being “things that guys probably will think are cool.” I entered the store and came across some Star Wars memorabilia, including an eighteen-inch-tall replica of Yoda, complete with white hair, green wrinkles, and tattered Jedi robes. It’s ironic to say that a replica of a puppet appeared lifelike, but this one did.

When I approached for a closer look, its head turned slightly to face me, its eyes blinked, and it said in perfect Yoda syntax, “Teach you to use the Force, I will.” I was impressed, and that was just the beginning.

Yoda instructed me, “Extend your hand before me.” So I did, hesitantly, not sure what would happen. The motion sensors at Yoda’s feet combined with animatronic motors in his body combined to fling Yoda backward more than a foot, as though pushed by the Force emanating from my outstretched hand.

My first thought was, “This is so cool!” My second thought quickly followed, “I have to have it!” Fortunately my third thought countered, “Danny, this serves no purpose whatsoever. And it’s a big box to lug through a terminal and continued business trip. And your wife will kill you.” I just smiled and filed away the experience to share one day. In all likelihood, my memory has embellished the story a bit, but the next part is clear: A few moments later I stepped into the men’s room, and after using the facilities, I joined a row of guys standing in front of sinks, waving their hands wildly to find the exact angle and position for the motion-sensing faucet to sense their presence and turn on the water. The contrast was striking: The Yoda replica’s sensors were so sophisticated that they made me feel like a Jedi for a moment, and a few paces away the faucet sensors were so lousy that it took ten minutes to wash my hands.

The future is here, it’s just not evenly distributed.

The future is here, it’s just not evenly distributed. This juxtaposition was a striking illustration of the story of progress. Digital Yoda was “amazing,” and a few paces away stood a row of men muttering, “Are you freaking kidding me?!” The future is here, it’s just not evenly distributed. The same is true of education and learning. That raises an important challenge for all of us: Even as we work to build a better tomorrow, how do we make the most of what is available to us today?

I have a soft spot for Disney animated movies. As a parent, I appreciate their balance of entertaining children and holding the interest of adults; as an optimist, I appreciate their hopeful view that things work out in the end; and as an educator, I appreciate the life lessons that they embed in simple stories. For example, consider the Circle of Life lesson in The Lion King, shared in the unmistakable baritone of James Earl Jones as Mufasa: “Everything you see exists together in a delicate balance. As king, you need to understand that balance and respect all the creatures, from the crawling ant to the leaping antelope.” Simba, the young lion who is heir to the throne, is puzzled. “But Dad, don’t we eat the antelope?” Mufasa replies, “Yes, Simba, but let me explain. When we die, our bodies become the grass, and the antelope eat the grass. And so, we are all connected in the great Circle of Life.”

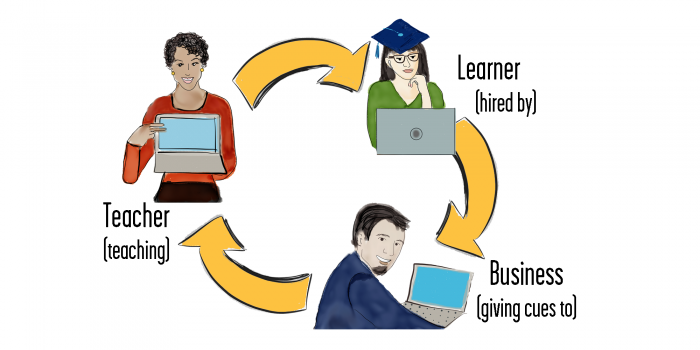

A similar Circle of Life exists in the world of education, with the three actors being learners, teachers, and businesses. Learners are instructed by teachers, who take cues from businesses as to what is needed and valuable in the work force. Those businesses then hire the learners.

What follows is advice to help each of these actors make the most of the opportunities available to us.

As a young student or at the start of your career, your imperative is to make an investment in education that yields a worthwhile return in the form of acquired skills and increased employability. To that end, consider carefully whether the signal of a university degree—especially if it’s not from a top school—is worth not only the cost, but also the opportunity cost. Remember that your time has value, and the opportunity cost of whatever else you could be doing if you weren’t at school is estimated at $54,000. As a thought exercise, consider that if at the age of twenty-two, you invest $54,000220 at a modest seven percent interest rate (which is the low end of the S&P 500 long-term average), by the time you’re sixty-five, it will have grown to more than $800,000. Set that against the cost and debt that you might incur, and you’d better be confident that it’s the right move for you.

Rather than a traditional college education, consider less expensive and more focused alternatives.

Rather than a traditional college education, consider less expensive and more focused alternatives. Rather than a traditional college education, consider less expensive and more focused alternatives, for example, a hybrid program like the one offered by Minerva Schools at KGI; a “last mile” training offered by MissionU; find an apprenticeship, either structured through a program like Praxis (whose slogan is “The degree is dead. You need experience.”), or independently, through a service like GetApprenticeship.com; or a coding boot camp such as Turing, Lambda, or General Assembly. They’re all likely to serve you in much better stead than a generic college degree. Most of them cost substantially less, and some tie your investment directly to your future employability by charging little or nothing upfront, but being paid a percentage of the job wage you land when you graduate. The total amount is still much less than college.

If you’re not sure what you want to do with your life yet, which is reasonable when you’re in your late teens or early twenties, consider taking a gap year, either on your own or through a structured program like UnCollege. Take the time to expose yourself to new ideas and fields of interest, which can be done easily and inexpensively through online courses or with books ordered from Amazon or borrowed from your local library.

Another option is to do free work to gain experience or look for internships and apprenticeships. You don’t need college to do this, and often the best positions must be found independently. To learn how to do this, look at Charlie Hoehn’s Recession-Proof Graduate. His suggestions work just as well in good economic times and for people who never went to college. The decision to skip college or drop out can be walked back easily if you decide to do that later; most colleges offer generous, flexible sabbatical and leave options, in which you can take at least a year or two off with no strings or consequences. Harvard, for example, allows you to come back anytime. Although much is made of famous dropouts such as Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg, the truth is that they knew they could return. If it makes you more comfortable, rather than drawing a hard “I’m out” line in the sand, consider a “soft dropout” of a year or two to explore better options.

Also keep in mind that you can do a bit of college on the side. If the core value of the signal of a degree is that you have the keyword in your resume for automated application tracking systems to read, you can apply to college, be accepted, and maybe take a course or two, because most ATS systems can’t tell the difference between “graduated with a Bachelor of Arts from Acme University” and “pursuing a Bachelor of Arts from Acme University.”

Make it a habit and a practice to keep learning, and stay engaged.

Of course, the journey of lifelong learning doesn’t end when you land your first good job. Make it a habit and a practice to keep learning, and stay engaged. Take courses that expand your skill set, and undergo training that challenges and broadens your thinking. There are countless examples of the former in every niche and industry. For the latter, some examples include Seth

Godin’s altMBA course, my company Mirasee’s Business Ignition Bootcamp (which is free; details at LeveragedLearning.co/bib), and Byron Katie’s training on The Work.

All of this will hold you in good stead and keep you both competitive and engaged. That said, the options available to students are only as good as can be created by dedicated and hard-working teachers.

Advice for Teachers and Experts

As a teacher and expert, your imperative is to stay current in your field, empower your students, and be well rewarded in the process. This begins by staying as active and involved in your field of expertise as possible. Read the news and the journals, follow the thought leaders, and do the occasional project or two. Without ongoing exposure, it’s just a matter of time until you get left behind.

With your expertise secured, lean into your role as a teacher. Think deeply and be creative about what is most important for your students to learn, what scaffolding they need to wrap their heads around whatever you’re seeking to share, and how to support them to encode that knowledge in a way that can be retrieved when they need it.

Most important, don’t stop at knowledge. Layer insight and fortitude into your curriculum, and teach your students how to get where they need to go, with the 4 Cs identified by the Partnership for 21st Century Skills: critical thinking, communication, collaboration, and creativity.221 It can be a tightrope act to strike the balance between giving students everything they need, but not so much that they need not ask questions or reach their own conclusions. Follow the lead of the Turing School of Software & Design, as recounted by graduate Bekah Lundy: “They give you a lot, but they don’t hand you anything on a silver platter.”222

If some of these suggestions feel impractical because of the environment in which you work and teach, find or create an environment that gives you freedom to innovate, whether that means teaching elsewhere or putting out your own shingle as an educator entrepreneur. If you choose the latter, a good place to start is one of the Course Building Bootcamps offered by my company Mirasee (details at LeveragedLearning.co/cbb).

Finally, since we’re still in the Wild West days of online courses and continuing education, do everything you can to lean into legitimacy. Work extra hard to ensure student success and capture those case studies. Align yourself with whatever bodies govern or lend credibility in your industry, and when you’re ready, seek their stamp of approval. Most important, build connections with the stakeholders in your students’ success. They include your students, but often they are businesses.

Advice for Business Leaders

As a business leader, your imperative is to find good talent, retain those employees, and train them to produce the best individual performance and collective culture of innovation. The first step in that direction is taking a long, hard look at what really leads to success and performance, recognizing that university degrees aren’t the key, Advice for Business Leaders services in the United Kingdom removed degree classification from its hiring criteria, citing a lack of evidence that university success correlated with job performance.223 Similarly, Laszlo Bock, former head of People Operations at Google, went on record saying that grades in degree programs are “worthless as a criteria for hiring,”224 and currently as much as 14 percent of employees on some Google teams never attended college.225

Grades in degree programs are “worthless as a criteria for hiring.”

Drop the application tracking system, or at least switch off the filtering related to education. While you’re tweaking your hiring process, lean more into the assessments and simulations that actually give you a sense of what candidates can bring to the table. When Ernst & Young did this, they saw a ten percent increase in the diversity of new hires.226

Most important, cultivate the things that matter by developing a culture of learning and growth. Great books abound on this topic, ranging from Dan Coyle’s The Culture Code, to Ron Friedman’s The Best Place to Work, to Laszlo Bock’s Work Rules!, and to Patrick Lencioni’s The Advantage. Some of these authors can be brought to speak to your organization, and Patrick Lencioni’s Table Group offers consulting and facilitation. Training also can be found from other providers, such as Mind Gym, The Center for Work Ethic Development, and my company Mirasee (focused on developing the strategic thinking skills of your employees and creating your own internal training; details at LeveragedLearning.co/business).

Most important, remember that talent comes in all shapes and sizes, and that the value of the degree you might have earned decades ago is very different from the value of degrees issued by institutions of higher learning today. As a business leader, it is your job to take the actions that lead your organization into the future, and this is how to do it.

Among our time’s greatest fonts of wisdom and inspiration is the red dot that sits center stage at the annual TED conference. Once reserved for the most exclusive and rarefied of attendees (those are still the people who attend the conferences), more than a thousand of these ten- to twenty-minute talks are available to watch online for free. So if you’re looking for a jolt of energy and optimism, spend a few hours on a TED talk binge. The talks present a world of promise and possibility, in which changing your perspective can extend your life,227 sense organs can be augmented or even replaced,228 and great leaders inspire action by Starting With Why.229

Then we close our laptops, take out our earbuds, and return to our lives, in which millions of people face debilitating stress and anxiety, far too many struggle with disabilities, and business news is about more scandal than success. Looking at the world around us, we can’t help but think wistfully of the hope offered in the TED videos, and wonder where it went.

The gap between the world that we live in and the world that we wish for is bridged by education.

The gap between the world that we live in and the world that we wish for is bridged by education. It’s not by degrees, not by debt, and not by signals that aren’t backed by substance. We need real education, which makes its beneficiaries more knowledgeable, more insightful, and possessed of the fortitude to see their way through challenges to reach innovation and success. That education is the real “golden ticket” for those who claim it, and with enough of these tickets in circulation, the ultimate winner is the whole of our global society.

As I wrote at the start of our journey together, every chapter in this book could have been an entire book, or several, of its own. Many of the ideas I’ve shared could be further expanded, and there’s a lot of work to be done. That work is for all of us to do. Seizing this sort of education in its current early state takes ingenuity from learners, dedication from experts and teachers, and vision from business leaders. Most important, it takes courage from all three. I recognize that some of these changes are uncomfortable, and some are downright scary, just as it is for trapeze artists to let go of one bar in order to reach the next. But it’s the best way for us as individuals to see the success that we want and need, and the only way for us collectively to build a better tomorrow.

“A responsibility we bear, and an opportunity we must seize.”

When I taught my first college course in 2003—a seminar on “Race and Gender in Mass Media” at a top-ranked university—it looked very much like the courses I’d taken as an undergraduate a decade prior.

I’d stand at the front of the classroom each week and ask probing questions, hoping to engage my 20 charges. I’d lecture from, and periodically glance at, my printed-out notes. I certainly wouldn’t screen a YouTube video (that hadn’t been invented yet) or invite them to engage on social media (ditto). All assignments were handed in on paper, and graded by hand.

Fifteen years later, the landscape has changed almost beyond recognition, both for college students and for the adult learners I now work with.

I still teach traditional classroom-based executive education programs, primarily for Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business. But I’ve also taught executive programs exclusively online, as well as in “blended learning” formats that mix webinars with an in-person component.

I’ve created online courses available outside academia, ranging from a 12-hour CreativeLive program on “Building Your Brand as a Creative Professional” to a 35-minute online course, completed in partnership with The Economist, on “Reinventing Yourself Mid-Career.”

I’ve developed more than a dozen courses for LinkedIn Learning (formerly Lynda.com), and have also created online courses that I sell directly to readers of my work, on everything from becoming a recognized expert to creating high-quality content more rapidly.

In short, I’ve experimented with almost every modern configuration of advanced learning, and have seen firsthand what works and what doesn’t.

That’s why I’ve found Danny Iny’s work, and the concept of Leveraged Learning, to be so valuable. For years, Danny has been a good friend and one of the smartest thinkers I know on the future of education.

I profiled him in my book Entrepreneurial You (Harvard Business Review Press, 2017), and followed his advice scrupulously when I was developing my own online courses, which have now generated multiple hundreds of thousands of dollars and impacted the lives of hundreds of talented professionals.

I’ve long agreed with Danny that our current system of education is broken. Back in 2013, I penned a Harvard Business Review article, “Grad School May Not Be the Best Way to Spend $100,000.” Danny is spot-on that while historically prominent Ivy League schools will continue to prosper, and low-priced community colleges will continue to fill a targeted niche, there will be a massive shift in the middle coming very soon.

As he points out, “If an institution charges in the same range as Harvard and still sports unimpressive graduation rates, post-graduation employment rates, and low starting salaries for those graduates who do manage to find a job, the fact that they’re easy to get into for people who want a college experience will no longer do the trick.”

That means the “education-industrial complex” we’ve come to know for the past 70-odd years (since the end of WWII) is about to implode. The challenge before us is how to navigate these uncharted waters— as professionals, lifelong learners, and (perhaps) as teachers, professors, and maybe even as course creators ourselves.

Danny’s solution, which you’ve read in this book, is both wise and humane. For too long, many institutions (and individual instructors) took the easy path. They kept doing what had worked before, milking a profit and focusing more on their own needs or interests than what their students—their customers—wanted or needed.

Those times are past.

If we want to create a thoughtful, educated citizenry—and if we want, at a very basic level, for our own work to be effective and meaningful—then we have to get serious about understanding human behavior.

How can students, especially busy professionals who are now called upon to keep their own skills sharp over a lifetime, learn best? How can we create a learning environment that’s engaging, empowering, and effective? And how can we, as learners, create the time and mental space necessary to continually refresh our knowledge and abilities?

Having read Leveraged Learning, I know you’re better prepared to grapple with the critical questions we’re all facing about the future of learning in the twenty-first century. As a professional, you understand the irreplaceable value of lifetime learning—the necessary ingredient to stay not just relevant but ahead-of-the-curve in the marketplace.

If you’re also an expert and educator, you understand the critical importance of student engagement. It’s insufficient—and in some circumstances, even exploitative—to create materials and then let students flounder them through on their own. We have to create robust learn- ing communities, whether virtual or in person, that support student knowledge and growth.

And if you’re a business leader, you understand that these issues simply can’t wait. As the impact of technology and globalization deepens every day, we risk having a stagnant workforce ill-equipped to meet today’s most pressing business needs. We can’t rely on ‘the system’ to generate the high-skilled talent we need. We have to roll up our sleeves, get involved, and encourage and incentivize our employees to embrace transformative lifelong learning.

The shifts Danny has documented are disruptive, but carry within them the potential to reshape education dramatically for the better. It’s a responsibility we all bear, and an opportunity we must seize.

Dorie Clark

Adjunct Professor, Duke University Fuqua School of Business, and author of Reinventing You, Stand Out, and Entrepreneurial You

July 2018

New York, NY