The Six Layers of Leveraged Learning

Great chefs know that all dishes and flavors are created by some blend of the presence or absence of five basic tastes: sweet, sour, bitter, salty, and umami (savory). In much the same way, every learning experience is the product of six different components, each layered on top of the next: content, success behaviors, delivery, user experience, accountability, and support. Let’s explore each of them in turn.

The base layer of Leveraged Learning is the actual content of delivery, hence the emphasis of the Spencer and Juliani’s LAUNCH cycle on taking the time to get it right, which is informed by deeply understanding the problem and by having our sights clearly set on the goals we seek to achieve.

Michael Palmer, an associate professor and associate director of the University of Virginia’s Teaching Resource Center, created a program called the Course Design Institute to help professors better design their courses. This foundational exercise of their “backward-integrated design” approach to course planning is recounted in Chip and Dan Heath’s book The Power of Moments:

On the afternoon of the first day of the Course Design Institute, Palmer introduces an activity called the ‘Dream Exercise,’ inspired by an idea in L. Dee Fink’s book Creating Significant Learning Experiences. He puts the following question to his audience of twenty-five to thirty professors: “Imagine that you have a group of dream students. They are engaged, they are perfectly behaved, and they have perfect memories. … Fill in this sentence: 3-5 years from now, my students still know. Or they still are able to do. Or they still find value in.”203

We must begin with the end in mind.

We must begin with the end in mind. With a nod to the late Stephen R. Covey, we must begin with the end in mind, with a clear picture of what we want our students to know, feel, and do. That is the first of three steps, as laid out by Marjorie Vai and Kristen Sosulski:

- Begin with the learning outcomes. Check that the learning outcomes are the ones that are important and meaningful to the student.

- Work backward and plan out the assessments. In other words, how will we know (i.e. measure) whether our students have achieved the outcomes or not?

- Work backward again, to use the assessments as the measure of the content. In order to achieve these goals, what do students need to know? And how well do they need to know it? In order for us to impart that level of knowledge and skill, what do we need to communicate and share?

- Work backwards a third time, to the scaffolding they’ll need in order to understand. What knowledge and experience will make the training comprehensible and accessible to the learner. What is the background that you as the instructor take for granted, that might be beyond the student’s grasp. Most importantly, what can you do to bridge that gap for them?

- Prune your curriculum mercilessly. This is hard for creators of any kind, who often are enamored with their metaphors, examples, exercises, and turns of phrase. But it’s not about the content or curriculum or mots juste, but rather what will help the student. In the context of learning, there’s no such thing as content that is nice to have. Everything is either critical to the understanding and success of your students, or an opportunity for them to become distracted, confused, or overwhelmed. A big part of what makes the Tony Marsh Method for language learning so effective, for example, is that it dispenses with much of what is generally thought of as core to the language (i.e. grammar), and instead focuses on the goal of functional fluency. So get clear on exactly what needs to be taught to achieve the learning outcomes and nothing more, and heed author William Faulkner’s advice to “kill all your darlings” that aren’t serving the students’ goals.204

Now that we know what to teach, are we ready to move on to how? Almost, but not quite. First, there’s an important second layer of the course design process to explore.

At the start of every year, aspirations for a happier, healthier life prompt countless resolutions to start going to the gym. This leads to a rush of gym memberships, but sadly, the majority go unused.205 The same is true of the success rates of people who set out to quit smoking, learn to play guitar, and complete courses they’ve signed up for. The reason is simple: It’s hard to change behavior. As the adage goes, “To know and not to do is really not to know.” This poses a double challenge for educators in the era of volitional learning: We not only need to design learning experiences that empower students to apply and succeed with whatever we’re teaching them, but also we have to design a learning experience that instills the behavior of actually consuming and completing the course.

A course that students don’t complete, or one that students do complete but don’t implement, is of little value.

A course that students don’t complete, or one that students do complete but don’t implement, is of little value. A course that students don’t complete, or one that students do complete but don’t implement, is of little value. For that reason, the second layer of Leveraged Learning is the success behaviors that will see the student through to the finish line. This is so important that out of a list of twelve research-informed strategies that “every teacher should be doing with every student,” nearly half address specific success behaviors:

- Give students more opportunities to reflect on their learning and performance.

- Teach that the way students choose to study can hurt their ability to learn for the long term, and self-testing is more effective than reading notes. In other words, help students develop an awareness and understanding of effective learning strategies, so that they can take ownership of their own learning process.

- Teach that sleep is critical to memory consolidation.

- Teach students that effort matters most, and that neuroplasticity means they have the ability to rewire their brain to make themselves better learners.

- Teach students to recognize how stress, fear, and fatigue affect higher-order thinking and memory via the limbic system.206

While the list of possible success behaviors is almost infinite, we choose the most important ones by thinking through what is most likely to prevent students from consuming what we teach and applying what they learn. Sometimes success behaviors are simple and logistical; for example, instructing students to block time off in their schedules each week to complete the course work is both easy and effective. But in other cases, this can be much more involved.

Building Fortitude into Education

This is one of the areas where fortitude shows up most powerfully in education. If we know that students will encounter challenges, setbacks, and discouragement, we can arm them ahead to cope. This can be as simple as helping students anticipate what might happen and how they might feel about it, so that they have an effective response prepared. Peter Gollwitzer’s research has shown that this “behavioral preloading” can be surprisingly effective, as recounted by Chip and Dan Heath:

The psychologist Peter Gollwitzer has studied the way this pre-loading affects our behavior. His research shows that when people make advance mental commitments—if X happens, then I will do Y—they are substantially more likely to act in support of their goals than people who lack those mental plans. Someone who has committed to drink less alcohol, for instance, might resolve, “Whenever a waiter asks if I want a second drink, I’ll ask for sparkling water.” And that person is far more likely to turn down the drink than someone else who shares the same goal but has no preloaded plan. Gollwitzer calls these plans ‘implementation intentions,’ and often the trigger for the plan is as simple as a time and place: When I leave work today, I’m going to drive straight to the gym. The success rate is striking. Setting implementation intentions more than doubled the number of students who turned in a certain assignment on time; doubled the number of women who performed breast self-exams in a certain month; and cut by half the recovery time required by patients who had received hip or knee replacement (among many other examples). There is power in preloading a response.207

Consider the challenges that your students will face, devise a success behavior that can carry them through (ideally by looking at existing bright spots), and then backtrack through your curriculum to insert and instill those behaviors before students need them. With that in mind, we’re ready to turn our attention to delivery.

When it comes to the delivery of a high-quality educational experience, there are many ways to get the job done. Say you want to teach how the modern economy works. Is your best bet to teach an extended college course on micro- and macro-economics, or write a series of research papers? Or would your students be better served by a 138-page narrative,208 a 31-minute YouTube video,209 or even combining online games with creative explanations?210 The answer will depend on the specific objectives and students, but odds are that the brute force of long courses and research papers isn’t the best way to go. To paraphrase a common saying, our students would benefit from our taking the time to create a shorter learning experience.

We must take the time to explore the metaphors and examples that best scaffold the learning that we seek to create, and we must consider the level of skill and fluency that our students need to achieve. Juliani and Spencer identify seven stages to the consumption and integration of knowledge:

- The first, exposure and passive consumption, which leads to,

- Active consumption, followed by,

- Critical consumption, i.e. consumption combined with critical evaluation of what makes sense and how this fits into what the student already knows. This is followed by,

- Curating, which is an active selection of which pieces are worth keeping and which pieces are worth abandoning. Then comes,

- Copying and modifying, and then,

- Mash-ups, which (like copying and modifying) involves taking something learned and making it your own. Finally, we arrive at the pinnacle of learning, which is the ability to,

- Create from scratch.211

The upshot is that deep learning, real understanding, and the development of competence all involve the active participation of the student in the learning process. That doesn’t just happen, it must be intentionally designed into the delivery of the curriculum. As articulated by Vai and Sosulski:

Learning is not a spectator sport. Students do not learn much just by sitting in classes listening to teachers, memorizing prepackaged assignments, and spitting out answers. They must talk about what they are learning, write about it, relate it to past experiences, and apply it to their daily lives. They must make what they learn part of themselves.211

"They must talk about what they are learning, write about it, relate it to past experiences, and apply it to their daily lives."

"They must talk about what they are learning, write about it, relate it to past experiences, and apply it to their daily lives." Find your metaphors, craft your explanations, and then create opportunities for students to practice and apply what you teach them, whether that’s through activities or assessment. On the activities side of things, Vai and Sosulski offer a list of options, including discussions, journal writing and blogging, project-based learning, simulations, debates, portfolio building, offering critiques, conducting primary or secondary research, and delivering presentations.212

If students can’t immediately practice what you preach, a great tool in the teacher’s toolbox is formative assessment with in-process evaluation of comprehension, learning needs, and progress. Offering this sort of frequent, low-stakes feedback on understanding helps students to consolidate and retain what they’re learning. This is supported by the research of John Hattie, author of Visible Learning, who analyzed hundreds of meta-analyses of student achievement studies and found that formative assessment ranks third highest out of eight hundred fifteen factors.213

So far we’ve covered what to teach, how to support students through the process, and how to deliver the training. Now it’s time to pack it all together into an effective user experience.

For most of the past few centuries, the experience of education remained pretty much the same: A teacher at the front of a class lectured to a room full of students. Sure, there was variation in terms of the expertise and visual aids of the teacher, the age and skill of the students, and perhaps the reference materials and note-taking equipment at their disposal. But by and large, the students showed up, listened to the teacher, wrote down their notes, and did some reading and homework, either alone or together with their peers.

However, in the past couple of decades, things have changed at a dizzying pace. The students may be remaining in a classroom, or sitting at home in front of their computer, or even out jogging and listening through their earbuds. The instructor may be delivering the lesson in real-time, or using a recording made weeks or years in advance. Students may meet in person to collaborate, or they may use a telephone, a messaging tool like Slack, or a video conferencing tool such as Skype or Zoom. They may read books and articles, or watch videos, or listen to audio recordings, or even participate in virtual or augmented reality simulations. Students may be digital natives who are fluent in all these technologies, or baby boomers who feel bewildered by it all, or anywhere in between. The same is true of the instructor.

Navigating this landscape is challenging for two big reasons. The first comes down to technology; the landscape continues to change rapidly, and instructors feel as if they’re constantly playing catch-up. Often they need to work with a myriad of tools of different levels of maturity, which may or may not coordinate smoothly. But this is a problem that will disappear with time. As learning expert Jonathan Levi shared with me when I interviewed him as part of the research for this book, “online learning in 2018 is where the Internet was in 2001. It’s just a matter of time before we have things like pupil movement and dilation tracking to measure engagement, ECG readings to measure learning, and so on.” Whether the technology gets quite that far, we can be confident that as technology matures, it trends toward an easier user experience. So we do our best, and over time our best gets better.

The bigger challenge is that of frame of reference, which puts blinders on our thinking that we don’t even know are there. A case in point: Many North American educators implicitly assume that a single teacher can handle as many as twenty-five students. Where did this number come from? The surprising answer is a determination made in the twelfth century by the Jewish scholar Maimonides (who, incidentally, taught students in an oral tradition of chanting Torah and engaging in Talmudic studies. Not a typical classroom even in the twelfth century!). There are two categories of blinders that course creators must be extra wary of.

Real-time and in Person Vs. Semi-synchronous and Online

The risk of taking education online and semi-synchronous is that we still design it as though it is real-time and in person. This means we create a poor man’s version of an in-person classroom, which isn’t a great learning experience. Here are a few features that are made possible by the semi-synchronous and online nature of modern education:

- Different students at different levels of skill and experience can concurrently work their way through adaptive learning paths, in a “choose your own adventure” flow-chart lesson hierarchy.

- Lessons don’t have to be forty-five or sixty or ninety minutes long, nor do they have to be delivered on a weekly basis. Any lesson length is possible, based on what is best with the material, and any pace is possible, based on what is best for the students and the work they need to complete.

- Every student doesn’t have to consume the training in the same way. Some can watch videos, some can listen to audio, some can read transcripts, and some can mix and match.

Desktop and Intentional Vs. Mobile and Interstitial

This is a newer blinder, but no less challenging. For most instructors, when we think digital, we think computer, an assumption that is sorely out of date. Already the majority of Internet traffic comes from mobile devices, not computers.214 This isn’t just a difference in screen; it’s a difference in consumption pattern. With computers we’re typically seated at our desks, focused on whatever we’re trying to do (like writing a book). With mobile devices, we’re typically on the go, with our attention split between the content on our screen and whatever we’ve taken a short break from to attend to it.

This isn’t just a difference in screen; it’s a difference in consumption pattern.

This isn’t just a difference in screen; it’s a difference in consumption pattern. Author Dan Pink describes how this has divided content into two broad categories: intentional and interstitial.215 In the context of television, intentional content is the stuff that you wait to watch at home, on the couch, with your spouse beside you and a bowl of popcorn on your lap. Interstitial content, on the other hand, is the stuff that you’ll watch in five-, ten-, and fifteen-minute bursts, while you’re waiting in line at the grocery store, killing time in an airport terminal, or chilling out at Starbucks.

The implications for learning are profound, because inside most learning experiences are some components that require and justify intentional consumption, for example, the final assignment at the end of a module. Also, there’s content that can just as easily be consumed in bits and pieces, like the lecture that can be listened to in four separate sittings. As instructors, we must be mindful of all this and intentionally design for it.

On September 5, 2010, I joined twenty-one thousand participants at the starting line of the Montreal Marathon. It was a beautiful day, and we were all excited when the starting bell rang. I ran at a brisk pace, enjoyed the fresh air, and high-fived the volunteers at the early mile markers.

Then I started to get tired. The distance between racers increased as initially small differences in pace added to a differences in distance and time. I discovered that I hadn’t trained nearly as long or hard as I should have, and I was feeling that deficit. But I pushed through, sometimes running, sometimes walking, but always moving forward.

Around the twentieth mile, I hit “the wall,” the sudden wave of fatigue that sets in toward the end of the race and threaten to crush you. I barely persevered and limped over the finish line with the thoroughly unimpressive time of about six hours. At many points along the way, I was tempted to quit. The race was long, I was tired, and my legs ached, so quitting would have been easy. Why did I keep on going?

Part of the reason was a commitment to myself, part was the context of all the racers all around me, and part was the accountability to all my friends who knew I was doing it. I would have to tell them that I had quit, and that was a distinctly unappealing idea. But the most important factor by a wide margin was that I ran the race with my then-girlfriend and now wife! This reversed the effect of an insidious challenge to behavior change: hyperbolic discounting.

The Challenge of Hyperbolic Discounting

Daniel Kahneman was born in Tel Aviv in 1934, where his mother was visiting relatives. He grew up in Paris, France, and spent much of World War II on the run from the Nazis. After the war, in 1948, his family moved to British Mandatory Palestine, right before the creation of the state of Israel. He studied psychology at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, and then earned his masters and doctorate at the University of California, Berkeley.

The year 1977 was an important one for Kahneman. That year both he and his colleague Amos Tversky were fellows at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University, and a young economist named Richard Thaler was there as a visiting professor. That sparked his interest in the burgeoning field of behavioral psychology, which led to ground-breaking work that won him the Nobel Prize in Economics, and was documented in his excellent book Thinking, Fast and Slow. The crux of his research was the strange apparent irrationality of human behavior, as a function of various cognitive biases. Hyperbolic discounting is one such cognitive bias, which is at the root of why accountability is so important in course design.

Hyperbolic discounting essentially means that we give more weight to consequences that are immediate than to consequences that wait for us further in the future. For example, given the choice between ten dollars today and eleven dollars tomorrow, most people choose eleven dollars. Given the choice between ten dollars today and eleven dollars next year, though, most people go for the ten dollars today. It’s the logic of “better a bird in the hand than ten on the bush.”

Hyperbolic discounting is the root of the challenge with doing coursework, training for and running a marathon, and pretty much every other thing that we want to do and know is good for us: the benefits are far off into the future, but the cost is right here, right now. Next year I’ll be glad that I finished the marathon, but right now I feel like quitting. Tomorrow I’ll be glad that I went to bed early, but right now I want to watch a few more episodes of Game of Thrones. As a species, we aren’t very good at choosing what we want over what we feel like in the moment.

Accountability is so important because it reverses the effects of hyperbolic discounting, by adding both pleasure and pain that enforce the immediate decisions we actually want to make. Sure, I’m tired and I feel like quitting this race, but I’m enjoying the company of my peers, and the physical pain in my legs doesn’t hold a candle to the emotional pain of quitting in front of my girlfriend!

Accountability, along with the community that provides it, is among the most important factors that keep us on target moving toward our goals. Conversely, a lack of accountability and structure is one of the greatest challenges in the transition from mandatory to volitional education; if I can choose to watch lesson materials and do the work on any day of the week, in any week of the year, in any year of the next decade, then the odds that I won’t do it at all increase dramatically. This makes it incumbent on educators to build accountability into our learning experiences. A couple of easy ways to do this are forcing a minimum progression speed and raising the stakes:

Forced minimum progression. Sometimes the simplest solution is to take away some of that extra choice. Adding some structure to a program in which everybody starts on a certain date, must meet certain deadlines, and completes the program together can have a dramatic impact on completion rates, as is the case with Seth Godin’s altMBA workshop214 and my own company Mirasee’s free Business Ignition Bootcamp.

Raising the stakes. This is implicit in the previous suggestion (such as if missing a deadline has consequences), but can be taken to a whole new level. An extreme example is a commitment contract, described by Ian Ayres in his book Carrots and Sticks: committing yourself to donate money to a cause that you despise (an “anti-charity”) if you don’t meet your commitments. This draconian approach is effective but difficult to get students to get onboard. Thankfully, it often doesn’t take that much effort to prompt action. For example, in one of the programs that my company offers, a missed deadline would add an icon of a frowning face to the student’s course portal. There was no tangible consequence, but that frowning face was enough to affect student behavior.

Accountability is a powerful way to keep students moving forward, but be careful about applying it to compensate for other challenges in your course design. If students are getting stuck because of technology issues, the promise of an incentive or the threat of a penalty might be enough to get them to overcome the issue. However, it’s often easier to fix the issue and eliminate the problem altogether.

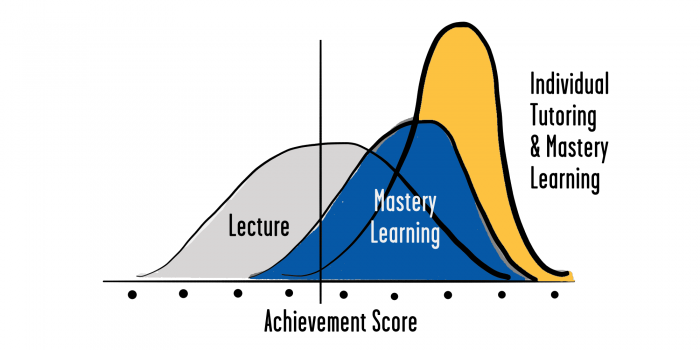

In 1984, educational psychologist Benjamin Bloom set out to measure the impact of mastery-based learning (meaning that students wouldn’t progress to new material until they mastered the old material) and one-on-one tutoring on student achievement. He compared a regular classroom as the control with a lecture-based classroom that followed a mastery learning approach as variation A and a classroom with a mastery learning approach and one-on-one tutoring for students as variation B. The results were staggering: Variation A performed one standard deviation above the control, and variation B performed two standard deviations above the control.

“The average tutored student was above 98 percent of the students in the control class.”

“The average tutored student was above 98 percent of the students in the control class.” In Bloom’s words, “the average tutored student was above 98 percent of the students in the control class.” This was a true breakthrough: a way of supporting 98 percent of the students to perform substantially above the current average. The challenge, of course, is the lack of money and teachers to provide one-on-one tutoring to every student. Statisticians use the Greek letter sigma to represent standard deviations, which led to the naming of Bloom’s 2 Sigma Problem: “to find a method of group instruction as effective as one-to-one tutoring.”217

Now, finally, technology and ingenuity are converging at a place where this problem can be solved. As Ryan Craig writes:

Combining adaptive learning with competency-based learning is the killer app of online education. Students will progress at their own paces. When they excel on formative assessments integrated into the curricula, they are served up more challenging learning objects. And when students struggle, adaptive systems throttle back until they’re ready for more. Adaptivity helps students build and maintain confidence, which leads to flow.218

The solution isn’t just technology, but rather an intelligent integration and handoff between technology and human support. First comes mastery-based instruction, which means the student doesn’t progress to lesson two until she’s understood lesson one. The first step is to check on the comprehension and performance of a student and offer corrective feedback. This can be done not only by technology but also by peers. As Coursera co-founder Daphne Koller explains in her excellent TED Talk, correctly structured and administered peer feedback structures yield the same returns to students as feedback from the teacher.219 The best part is that students tend to learn the most from the process of providing feedback to their peers. When the peer feedback isn’t enough, or a persistent issue arises, the feedback can be escalated to the support of a tutor or coach. The key isn’t to avoid human support, but rather to apply it where it has the potential for the greatest leverage and impact.

So you start with content, layer on success behaviors, plan your delivery, design a user experience, craft elements of accountability, and offer support where it’s needed. This is the recipe for a great learning experience for students, but still, an educator’s job is never done.

Want to test your understanding of the ideas that we just covered? Or start conversations with interested friends and colleagues? Here are a few questions to guide you:

- What are the six layers of Leveraged Learning?

- What are the four steps to determining the content of a course?

- Researchers have found that “behavioral pre-loading” through implementation intentions is a powerful way to get people to follow through on their goals. How can this be applied when designing a curriculum?

- According to John Spencer and A.J. Juliani, what are the seven stages to the consumption and integration of knowledge?

- What is “formative assessment”?

- Technology is advancing at a dizzying pace and creating blinders on educators’ thinking about how to design learning experiences. What are are the two big categories of blinders that course creators must be extra careful of?

- What are the two broad categories of content consumption according to Dan Pink? How are they different from each other?

- What are two ways for educators to build accountability into learning experiences?

- According to the research of Benjamin Bloom, which intervention resulted in student performance that was two standard deviations above the control (lecture-based classroom)?

- What, according to Ryan Craig, is the “killer app of online education”?

- What does an intelligent integration of technology and human support look like?

Like What You Read, and Want to Go Deeper?

Here are a few good books to take a look at if you’d like to go deeper on some of the ideas presented in this chapter.

- Julie Dirksen’s Design For How People Learn

- Peter Hollins’ Make Lasting Change

- Marjorie Vai and Kristen Sosulski’s Essentials of Online Course Design